Colin Peasley OAM is regarded as one of the great character dancers on the world ballet stage of the last 50 years. In this archival interview from 2004, he gives a unique insight into the art for which he is internationally celebrated. Originally published at bbdance.com.au 30/03/2004.

“I have never believed that character roles weren’t important. These days they tend to be devalued and I can understand that because if you spend ten years learning to point your foot and to jump up ten feet and turn in the air, then somebody says, ‘I want you to stand here, make two faces and walk off.’ – that doesn’t seem to be what you’ve been working for. I can understand why dancers don’t like it…” Colin Peasley

Colin Peasley’s forty year career on the ballet stage is a unique achievement not only for its longevity but for the sheer magnitude of its phenomenal creative output. Peasley is blessed with a genius for characterization that has enabled him to tackle an extreme range of roles from over-the-top to minutely understated – fops, friars, diplomats and witches. Whether he is an actor who became a dancer or a dancer who transformed himself into an actor is a moot point. The facts are that he is most definitely a dancer and, without question, also an actor. This interview focuses on Colin’s approach to characterization and performance in general, speaking candidly of his many experiences, including working with Nureyev, Bruhn, Helpmann and Graeme Murphy.

My primary interest in theatre has always been performance, and if I can borrow Graeme Murphy’s notion that “every life must have a theme song”, at the back of my mind, the late Bon Scott struts through the ACDC anthem Show Business on an endless loop.

While Bon Scott was involuntarily retrenched by the Grim Reaper, regrettably, in most instances, the ballet dancer tends to choose retirement from the stage just as his or her expressive powers start to develop along strongly individual lines.

Ironically, however, it is the story ballet – the art’s most traditional form – that has allowed the older dancer to have a presence on stage and accounted for some of the best dance performances I have ever seen. This, of course, is in the capacity of the “character” role, a part requiring stronger acting skills than acrobatic ability but, because the performance communicates through movement only, I have come to regard this facet of ballet performance as the subtlest form of dance.

My interest in “character” roles goes back several decades to when I fell in with a group of ballet goers who were rabid Ken Whitmore fans. Whitmore, who was a member of The Australian Ballet (1977-84) and is now deceased, was doing character roles exclusively by that stage though he was still a relatively young man. His interpretation of Friar Laurence (Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet) filled the fans with reverential worship. His Widow Simone (Ashton’s Fille mal gardée) delighted them with its campy cheek and I still remember the season when Whitmore sent a quiver of excitement through his following by doing his make-up for this part to look like the new artistic director Maina Gielgud. It was as the foppishly brittle King of France in Prokovsky’sThe Three Musketeers that Whitmore impressed me most and it was through his work that I became interested in “character”. If Ken Whitmore was the tutor of my undergraduate experience of “character”, it is by watching Colin Peasley that I have reached postdoctoral fellowship.

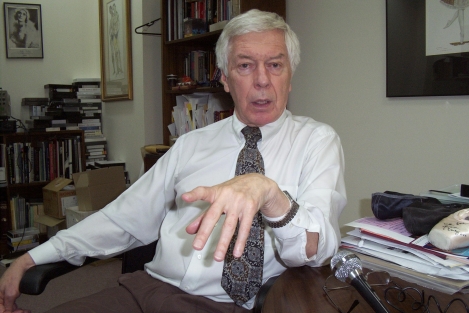

The following interview took place on Tuesday, March 16, 2004, in Colin Peasley’s office at The Australian Ballet Centre, where he is Education Programme Manager.

In The Australian Ballet’s early days, you danced your fair share of corps roles – peasants, gentlemen, czardas and pavanes – but you also appeared as Drosselmeyer in Casse Noisette (after Lichine, 1963) and as the Master of Ceremonies in Aurora’s Wedding (van Praagh after Petipa, 1964). Were these your first forays into character, how did you get the parts and what do you remember of the experience?

They weren’t my first character parts. I’d been doing character parts with Valerine Tweedie’s little amateur group in Sydney and when I was learning, I danced with a lot of amateur companies, which is the only thing that was around in those days. So, I tended to do works for the Halliday sisters – they had a group called the Sydney Ballet Company; something run over in North Shore, which was called Sydney Youth Ballet and I played the wolf in Peter and the Wolf for that and various roles like that. And even on television, for instance, I did Kastchei in The Firebird on ABC television. I’ve always had a penchent for acting and I think this is probably what Peggy van Praagh saw in ’63 when she was casting Nutcracker and possibly I was the oldest corps de ballet dancer there (Colin was born in 1934) and that may have influenced her, too.

The roles were wonderful and they were very fulfilling and and I have been very lucky in my entire time that I have never believed that character roles weren’t important. These days they tend to be devalued and I can understand that because if you spend ten years learning to point your foot and to jump up ten feet and turn in the air, then somebody says, “I want you to stand here, make two faces and walk off,” – that doesn’t seem to be what you’ve been working for. I can understand why dancers don’t like it but it worries me that artistic directors and reproducers of ballet don’t always give character work full credit.

Can you tell us more about the ABC production of The Firebird – who mounted it?

It was done by Valrene Tweedie in Sydney and at that stage I was working for the ABC as one of the ABC permanent dancers. We worked for Light Variety, it was called something like that and the producer was James Upshaw. We did all of those Dick Bentley shows, Make My Music and a hundred different shows. Occasionally, we did a serious work and Firebird was one of them.

Who danced the Firebird role?

It was probably Ruth Galene because she was ballerina at the time and did a lot of those things.

I always think of you as having “started” with Bodenwieser. How did you get into dance and how did you get to Bodenwieser?

Dance was a very big problem. In the 1950s. when I wanted to dance, it was looked upon as very strange if a fellow wanted to dance. I’ll go back on that: if I had said to my father that I wanted to be a violinist, or an easel artist or anybody in the arts, I would have been looked upon as strange. Artists were seen as long-hairs, as a bit weird. To ask to be a dancer was something that was not allowed. So, one: it hadn’t crossed my mind because it was taboo, and two: if it had, I wouldn’t have been allowed to do it anyway.

However, my sister wanted to do her début – it was a time when people “made their début” – and she needed someone to partner her in the formation waltzes and things you had to do to make your début and so, I took up ballroom dancing and caught the bug from that.

While I was ballroom dancing, I went through all those medals: gold bars, gold stars, every award possible, because I’m obsessive in all I do and then I started exhibition dancing. Well, in exhibition dancing you have to pick the girls up and throw them around and put them down; I was picking them up all right but I couldn’t put them down without falling over, so, I went to an adagio teacher, and the adagio teacher was on the floor above the Bodenwieser studio. One day when I was coming down, the studio door was open. I looked in and saw real dancing for the first time. Real dancing because the whole body was being used. They were throwing themselves to the floor and doing all sorts of wonderful things. It was a time when there were some really interesting women in there and I was amazed as I stood in the door. That was a stupid thing to do because boys were like hen’s teeth, so, any boy who stood in the door and looked like he might be interested, was about to be dragged in and inducted. And I was dragged in by Gertrud and I was told I must join the group instantly and I did. And I loved every minute of it because it’s expressive; ballroom dancing is not expressive. So, it probably gets back to me wanting to be an actor all the time.

Can you put a year to that encounter?

Yes it was probably 1958, maybe’57.

Can you name some of the women in the company at the time?

One person was Moira Claux, whose father opened the first nudist colony in Australia and I remember her because there was always a flash of breast around, which I thought was absolutely wonderful and kept me there even more than what dancing did. Others were Coralie Hinkley, Eva Nadas, Margaret Chappel and Anita Ardell. Keith Bain was the only male dancer who kept on going.

What is the legacy you took from Bodenwieser?

The fact that it was true dancing, that it involved the whole body. It brought out the fact that dance is a communication. Ballroom dance isn’t really a communication; it’s nice to do and it’s a social way of getting around but it’s not a communication like modern dance. I thought Bodenwieser’s approach to the teaching of dance was amazing, mainly because she was a woman who had a Graeme Murphy approach to creation. It just flowed out. I’ve never seen things flow out of a person as fast as this. She was a funny little woman, who was always in mourning. She used to always wear black in mourning for her husband who died in a German concentration camp. She would wear what was called “summer suits”, with little slackey-type trousers and a little veil over her eyes. And, if you fell over – I thought this was the best thing ever – she would immediately take you into the office and give you a little sip of sherry. I kept falling over all the time and that’s why my mind’s gone now, from her helping me on falling over!

It was theatre, really good theatre.

How would you describe Bodenwieser as an artist?

Being a middle European, being Austrian, Bodenwieser’s modern dance was entirely different to American – which I didn’t know at the time. It wasn’t about everybody becoming clones of Martha Graham, or clones of some other choreographer. Martha Graham built her technique on her own body. The middle Europeans tried to bring out your movement qualities and they did this through improvisation, not only single improvisation but group improvisation. Every Bodenwieser class finished with some improvisation. It may have been just Bela Dolesko (Bodenwieser’s musical associate) playing something on the piano while we interpreted the music, or, it may have been a story like the Three Wise Virgins, which we did regularly. I don’t know what a “wise virgin” is but we would do these biblical tales and we would make up dance to it. I found this liberating.

And what would you say about her as a person – after all she was instrumental to your serious start in dance?

I got to her very late in life, because you know she died in ’59, so she probably wasn’t a very well woman. But I still marvel at the way she had been able to transpose modern dance from Europe into the colonies – can you imagine coming from such cultured places, firstly to New Zealand and then over to Sydney, then starting from scratch, her group going around on the Tivoli circuit – it must have been horrendous for her. And she had enough impetus, enough strength and enough drive to get this going and to start a modern dance group in a really foreign soil.

But you could also turn that around and say that it must have been very inspiring and even exhilarating for her to come to a place where she was clearly so welcomed. Consider the people who gravitated towards her and the fact that she left such an enormous legacy, it must have somehow been rewarding for her, too?

Yes, that she was the sole perpetrator of all this meant that she had nobody competing but then that’s also a problem because half the thing about modern dance or any art form is that you need other input, you need to digest other sources to find out whether you are going right, or wrong, or just regurgitating what you’ve done. These days you can see videos and things; she never saw anything like that.

It’s an unimaginable leap from Bodenwieser – modern dance pioneer, avant garde artist – to custodian of character interpretation for a major classical ballet company – or is it? Can you explain?

Yes, but I think people misunderstand what modern dance was like in the ’50s – it was still based on stories. Even Martha Graham’s early works were all stories and Doris Humphrey’s and all of those people’s. So I didThe Imaginary Invalid for Bodenwieser, we did Errand into a Maze. They were basically stories, they may not have been a Dr Coppelius story but they were still places where you had to define the character and portray that character to make that work sensible. So it wasn’t such a big trip at all.

In fact, I would say it gave me better insight into what character work was. Bodenwieser didn’t have a corps de ballet; you didn’t stand at the back, in fifth position with your arms in a demi-seconde looking beautiful – everybody was contributing so that even when you were a crowd you were focusing towards the centre. So, to come into a ballet company where people just stand in lines and look mindless, I found unbelievable. So, too, the fact that people actually had to come around and say, “in this part, when Giselle comes on, everybody’s got to focus on Giselle…”.

What about the fact that the style of technique you would have used with Bodenwieser was not as regimented as that of ballet? How much freedom did that allow?

She did start with a ballet barre. Her classes started at the barre, not accenting turnout as much as classical ballet does but we did a barre to start the work on an ordinary day. As soon as we left the barre, her center work was always inventive; she could make an entire class out of one step: you’d do the step in different ways, with different accents, with different rhythms, with a jump in it, with a turn in it, you could do it as a progression, as a group thing. It’s amazing how she could develop one movement into all of these things. Although, I know what you’re talking about – classical dance is terribly regimented – her approach, I think, was nowhere near as regimented. Since then, I’ve done Martha Graham classes and they’re as regimented as possible, very codified. And, it’s a problem.

Classical ballet is a step system and by that I mean “we call this a glissade, we call this an assemblé, that ajeté. That’s a strength but it’s also a great weakness because words don’t mean the same to everyone. For instance, old to a ten year-old is an 18 years-old; old to me is someone 118. So, if I say to somebody, “I want you to do a glissade assemblé,” they’re drawing on their knowledge of what this is and it may not be what I think it is. This is where modern dance triumphs – except for Graham – because they don’t give the steps names. They say, “I want you to slide out your foot and to join that leg to the other and I want you to jump up in the air and join the legs together and come down.” We just say, do a glissade assemblé – good shorthand but not always what you want. Modern dance has the advantage over this and luckily I was able to bring some of this intellectual concept to my classical dance.

When you are first cast in a role, how do you go about creating it – do you have an approach, a method?

I don’t, unfortunately. I wish I did and that I had been to NIDA, or one of those places where they teach you all those clever things. I certainly bought all the books and read them because I’m a reader. Possibly that’s the clue because when I want to get into a role, I read about it. These days you can also look at a video, but I prefer to read, and strangely I prefer to read crits about it rather than what somebody says about doing it.

Going back to James Upshaw, I remember when we were doing those ABC shows, they were straight to air, there was no video tape then, in fact they would use a thing called a kineoscope, where they would take a film of a TV set and that would go around as a film to be shown in other places. It meant that any mistakes are out there. And James Upshaw did a hideous thing – on Thursday morning the whole cast and crew would assemble in the viewing room and we would watch the film of last week’s show. Then we’d go out and rehearse the next show straight after. That’s devastating because suddenly you realized that what you think looks like a young man in love with a girl, reaching across the table looking at her lovingly – we did a lot of those things with hands across the table while she’d be singing – actually makes you look like a sick cow. And you realize that what you think you’re doing is not being transmitted to an audience.

So, what a crit says they see in a performance is sometimes very good. When they say: “When Tom came on here, he doesn’t have the same sort of strength that so-and-so has but the softness he brought to the role blah, blah, blah…” and you think, I rather like that idea, I like the role being soft rather than hard and so you get ideas on how to develop things from what other people say about other people’s portrayal of roles. Or, from pinching other people’s ideas! I can’t tell you the number of things that I’ve pinched off Ray Powell or Sir Robert Helpmann that I think are good and I developed it to suit my body, my way. If I think it works, I take it! And I change things that don’t.

Do you ever incorporate things you see outside of theatre? For instance, I know that playwrights and poets may go to a public place and listen to the way people talk…

Yes, I’m an imitator of people’s walks. I look at how people walk and carry themselves, how movement manifests itself in different things. We all talk with body language and when you look at somebody who’s really upset at a party, they’ve just had a fight with their boyfriend or whatever and you see it happening and you see how the people group around, you think: “That’s really good” and I’m being a real bastard divorcing myself from the whole affair but analyzing it, which holds you in good stead. Some of the great stars of the past, who overdid it are also a great resource…

So, you’ve got an almost infinite resource in the world around you?

Of course, but only if you’re willing to use it. A lot of people don’t put the two things together.

The question I have wanted to ask for many years is about Gamache, that pampered, perfumed, satin-clad fop who wants to buy the young Kitri’s hand in Don Quixote – how did you learn the role, or, indeed how much of the character did you create from scratch when you first worked on it with Nureyev? Was it 1970?

We first started it in 1965 when we were overseas in Nice. Nureyev’s rival in Russia, I think (Yuri) Soloviev was having a great success with Basil and Nureyev wanted to dance Basil in the West, so he decided to do it. But we’d already committed to costumes, sets and learning all of Raymonda, so, in a pique, he went away and gave Don Q to Vienna (State Opera) when we said we couldn’t do two major works in one overseas tour. We didn’t get it until 1970.

When Nureyev first began teaching it to us, the role of Gamache was on Karl Welander. When he came back in 1970, he suddenly picked me. I’d seen Karl running round looking like I don’t know what – some sort of a twit and hating it – and I thought I can’t wait to get in there and do it because it’s a good role, for godssake!

Most of it was Nureyev. He was a wonderful mimic, a very clever choreographer and probably the only genius I’ve ever worked with. I think a lot of the things he did, he did out of spite, he didn’t like me that much. He used to call me “the black witch” for a story we won’t go into. When the costume came out, he fell about – he felt I was gift-wrapped. He kept saying, “More ribbons, make him bigger, make him larger!” But the costume really defines the character. When you put the costume on and that wig and that hat on and you’ve got the bloody sword and the gloves, there’s nothing else you can do but be a fop of that particular time. I think that was very successful. I loved working with him and the role. And, I’ve fought to do the bloody thing ever since!

You made Gamache somehow aged beyond the years you must have been when you did it for the movie…

Yes.

How did you come up with that?

The first thing was that he had no hair under the wig – there’s a point where the wig comes off and you see the bald head. Originally, Nureyev wanted to have syphallitic sores all over the head because in those days that was one of the reasons they wore wigs. All these dreadful things were on their heads and rather than wash or cure it, they just covered it up. So, obviously if I was syphilitic and aged and wearing rice powder to attract this young girl, it meant that I was an older person.

Why did they not have the syphilitic sores?

Dear Peggy thought it may have been going too far and I thought it may have been going too far, too, don’t you think?

How did you find Nureyev, the choreographer, to work with?

The man knew more about dance than anybody I’ve ever met. He was able to create female and male roles, and dance female roles incidentally better than most of the females. He was able to show them what was important in the step and how to bring this out. This was a clever quality.

I can’t imagine how any of our principals ever could achieve this, and this is not being rude to our principals mainly because when you’re on stage for your pas de deux and you come off, you go backstage to change or to rest. But he must have stayed in the wings all of those times in Russia, because how did he come out here and reproduce all those bloody ballets with 500 different people doing things all over the place – corps de ballet people that he probably didn’t give a stuff about but he knew all their steps, knew how it all went together. This is amazing. Kelvin Coe was another one. Kelvin Coe could dance everybody’s role in every ballet.

What is your most vivid, publicly admissible memory of Nureyev?

The stories are always good stories but they’re not what I remember him for. I remember him for being a superb artist on stage, for the times with Fonteyn doing performances that had the audience standing and cheering for longer than anybody’s ever had since. In Sydney, when he first came out, he did Corsaire in the old Elizabethan Theatre in Newtown and the 12-13 minute pas de deux would get 15 minutes of curtain calls. I’ve seen him come back and do the whole coda again. When was the last time you saw that?

Never.

This is a period we’re never going to see again. They’d say to him, “Are we going to do the coda again?” and he would say, “They’re not breaking chairs!” meaning they hadn’t stood up and jumped and yelled long enough. To be a part of that, to see the magic of these people – and you’ve got to remember we toured Europe with them as their backing group for three months, as well as the other times; for us this was a crash course in how to develop into an artist. It taught us all the good things.

At the same time we had people like Helpmann. During the filming of Don Q I would complain about having to come on to the set at six in the morning for make-up because I was too young-looking, I’ll repeat that “too young-looking”, and they had decided to spray me with latex, which wrinkles when it dries. Then on top of the wrinkled face they’d put this white make-up so that on camera you couldn’t see the latex and by the time I took it off at night, my face was like a prune. But it did make me feel old. So while I was bitching about that, Helpmann said, “What you’ve got to remember, Colin, is that we’re the ones getting the close-ups. Everytime they take Nureyev and Lucette, they’ve got to take their whole bodies and they’re way back. Who do you think they’re going to remember at the end of the film?”

Nureyev always got the publicity in the press. Once the dazzle of his initial appearance had been pushed into the background, he got the publicity for being a bastard: for slapping the ballerina, for throwing a tantrum, for making demands. But, if you say that all publicity is good publicity, could dance use a few more Nureyevs?

I think dance needs another Nureyev. I don’t think it’s going to get one for a while. And I say that because both Nureyev and Baryshnikov came out when there weren’t such good male dancers around so it was really easy to see the difference between Nureyev and everybody else even though, for instance, Garth Welch could dance almost as well but didn’t have the charisma and didn’t have all that publicity backing, which is part of this machine that makes you into a star.

Nureyev was treated like a rock star and acted like a rock star – all that thing of drugs and going to the clubs and the stories about him out at three o’clock in the morning with six or seven people on his arm. It was grist for the mill. Being over-the-top helped greatly but he couldn’t have been a star if he hadn’t been able to come up with the goods in dance. And very few people have the ability to walk on the stage and to attract your attention like that.

He’d walk on stage and some poor woman over here could be doing 32 fouettés and all eyes would instantly go to this man who just walked! Oh, come on! That’s wonderful, that’s charisma. That’s the star quality and today, even in film it’s gone. Where are those stars, the Bette Davises? It was a different time and in dance it was able to be done because the general standard of dancing wasn’t as high. For somebody to come out of The Australian Ballet and make you all go, “Wow!” is very difficult because all those principals are “Wows!” And there’s even a few corps de ballet that are “Wow!”

Yes, but I think there’s a difference in certain individuals. For example, you look at film of Baryshnikov doing something like the Albrecht solo from Giselle, in Dancers, which he does three times in succession in front of a mirrior and each version is identical and he’s consciously striving after that. There are not many dancers who have that level of control. So, you’re talking about unique genius and that flowers only rarely. Nureyev was quite the opposite, he would do it three times and do it completely differently and wow you again because of the variety…

Nureyev was amazing because he pushed the boundaries. He would hold the curtain between acts, while he went over and over things. He danced on second breath. I don’t know anybody other than Eric Bruhn, who did the same thing. By that I mean that most dancers will hold themselves back in class so they’d be fresh for the evening performance. But Nureyev would do a solo maybe six, seven times with the conductor on stage and things weren’t working. You’d think, oh God, what’s going to happen when the curtain goes up because no-one knew if it would work. It was like a circus with the excitement. Eric Bruhn would do the same thing but if it wasn’t working, he’d change it. So, if his double saut de basque around the room weren’t working, they’d become double assemblés! Or he’d change it so that when he went on stage, he was absolutely sure everything was going to work perfectly.

There are the camps of people who feel that Baryshnikov is superior or that Nureyev is superior, or, I know people who swear by Eric Bruhn as the ultimate dancer. Would you single out Nureyev?

Actually, Eric Bruhn’s the one that appeals to me because of his pure classicism and there was never anything that he did which didn’t look like it should have been photographed and put into a book on technique. Nureyev was interesting because of his personality and because he took huge risks. And Baryshnikov because he’s got this wonderful, easy jump and turning ability but, unfortunately, I didn’t think Baryshnikov had the intelligence of Nureyev. For instance, I think Baryshnikov does things in Giselle that no prince, real or imaginary, would do. I don’t think he has the integrity that Nureyev had but he’s still an amazing dancer, by God, I’m not taking anything away from him.

While there is no doubt that an interpretive artist evolves and improves over time, your Gamache has not altered radically over the years (comparing the 1972 film of Don Q with the most recent revival performance in 1999). Why is that?

When you do some roles, you’re not comfortable with them. There’s something that doesn’t click, you really haven’t discovered the person. So, you want to fiddle with it and experiment. With Gamache, firstly I was coached very well by Nureyev and I felt that the person who came out of that coaching is exactly the way Gamache should be. And, in spite of the fact that I’ve seen other people do it, I always felt our version was better. I think my character was more three dimensional, more rational that he was the sort of person who would have done those things, that he wasn’t camp, he wasn’t a figure of fun in himself, he was a figure of fun because he stood out against all the other people. He was an outcaste in that group. So, because I thought my interpretation was a good one, I’ve maintained it.

So the character becomes a personage, like Dame Edna Everage is a personage so that whatever the character does is automatically “ in character”?

I find the best character creation is the one that you’re not acting but the one you’ve taken and put on. So, when you go on stage, I could have had a really bad day rehearsing people or a really good day and part of that personality is reflected in the person you see on stage. I don’t try to divorce the way I’m feeling from the person, so he changes slightly in that way but the person himself is Gamache. It is a person, I know him, I could show you exactly who Gamache is right now.

When you play parts like Friar Laurence and Cardinal Richelieu (The Three Musketeers), both clerics but at the opposite ends of the moral spectrum, what in each instance do you focus on?

The first one, because of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, has a hell of a lot of things written about him but he is a peasant priest. He is not an educated priest. He makes dreadful decisions in what he does for Romeo and Juliet. I mean why did he marry them? Why did he let that happen when he knew it was going to cause all that trouble. Why did he make the vial of sleeping potion? These are dreadful things. Compare this with Richelieu, who is noble by birth and not only a cardinal but First Minister of the state, he was Louis XIII’s Prime Minister and he was a very powerful, very intelligent man but absolutely ruthless to the point of evil – destroying the Huguenots, basically starting the 30 Years War, making it so that Louis XIV can become the first absolute monarch. Richelieu is pushing towards that, doing dreadful things to those nobles, with spies everywhere!

They’re two wonderful characters. The first one because he’s a bit ditsy and the second because he’s got so much power.

Your Friar Laurence has a kind of naivety that is very absolving. Like you, I’ve wondered about why he does the things he does but he has a kind of innocence that drives him…

Exactly. Because he’s illiterate and because he’s a man of faith, and faith is very strong in him, he believes that God will handle all these problems. God will be on the side of right but God isn’t always on the side of right, unfortunately. Because these people should be together, doesn’t mean they will be and that’s where a lot of these religious people fall down. It’s not a rationally explicable God up there.

Your interpretation of Madge the Witch in La Sylphide is very subtle. How do you see this character and how did you arrive at your interpretation? I ask especially because you’ve already talked about Eric Bruhn, who was also such a famous Madge himself.

He actually did it here. It was the last performance before he died, which was a few months later.

Sylphide wasn’t taught to us by Eric. It was taught to us by Constantin Patsalas, who was a choreographer and a close friend of Eric. Madge was taught first on Paul De Masson, I think.

As the role of Madge developed over time, it turned into a caricature ( as Colin says this, he raises his hands like twitching claws, tilts his head to the side and distorts his face with a maniacal scary cackle ) and I can’t see how this could have happened in Denmark because they’re so famous for their actors and I can’t see how it could have happened when some who played Madge were women. I can’t see a woman doing this send up. So, when Eric started demonstrating things, my whole concept changed because I was angling towards that way anyway. When I saw Eric do it – he only did it on the Saturday night (premier season, 1984) – there was more power, more validity in this person being a pathetic old woman who has secret powers that she can use but she doesn’t go round throwing it out. She only does it when you tread on her. She is a mirror; if you’re nice to her, she’s nice to you and that’s why she says to those girls, “Oh, you’ll be married, you’ll be happy!” and all this. Then, when other people start to do things, she says, “No, you won’t marry her but you will…” The only thing that doesn’t really work there is in the witch scene when they are all going, “Agrh, agrh…” (Colin mimics the dancing demons), which seems a mocking of the whole thing. I’ve never been able to relate how I can do that less while everyone around you is doing all that grotesque dancing. Otherwise, I think the way I’m doing it works.

What is your favourite role?

I think my favourite role is the Baron in The Merry Widow ( This role was created on Colin in 1975). I love the Baron; I think he’s such a nice person. I love the way he won’t believe he’s being cuckolded, even though everybody is saying, “She’s doing things behind your back.” And he doesn’t believe it right up to the last act when he actually sees it happen. He is really brokenhearted but then when he goes out he says, “Come on, you’re young and he is young and I understand…” That’s really nice, I like him.

Do you have a favourite ballet?

No. And it’s because ballets are so varied and your moods are varied. I’ve seen this (current) performance of Mr B four times. I’ve always loved Serenade and if I was a female dancer, this is a work I would really love to do. Then, last night when I saw the show, I thought, no, Symphony in C would be the best one to do – it’s brash, it’s out there. If you feel romantic or soft, Serenade would be the one, or you feel dominant, like I normally feel, then Symphony in C. It depends on how you feel. But I love Giselle, which is a master work;Les Sylphides, which we don’t do anymore – please God, let it come back Raymonda, which has a stupid story but the most beautiful dancing. And I don’t want someone else to do it; I don’t want them to ask a contemporary choreographer to put on a new production. I want the Nureyev steps, based on the Petipa because it’s the dancing that I loved.

Would it be possible to restage it?

Well, yes. We have the notation, even though Nureyev is dead.

As a performer, do you stew before or after performances, if ever?

I do both and I still get very nervous before a performance and the dancers in the company find that amazing. A dancer gets nervous because they realize they might fall over in their pirouette or their jump may not be as clean as they want it; they think because you’re doing an acting role, there’s nothing to get nervous about.

Acting roles always have a lot of props. You’re always handling a lot of things and, quite honestly, if you muck something up, then you’ve made the story ridiculous. So, I still get nervous and while I don’t stew, sometimes at the end of performances, I think, “Oh that should have been done and why did she look at me at that stage, the timing of that is really out…” Acting on stage isn’t really acting, it’s reacting and if the person you rely upon to do something – so that you can react to that something – mistimes, or does it wrongly, it makes your reaction stupid.

Again, this is something not all artistic directors realize. We had one director who would take one of the principals into a room and rehearse the entire Giselle mime scenes just with this girl, without an Albrecht, without Hilarion or anybody else around. So, when the dancer went into a full call, she would be curtseying on the count two and a half, and be running away laughing on the count of three, no matter what Albrecht did. A nonsense! The curtesy has nothing to do with the count of two and a half; the curtsey has to do with “Thank you, sir,” for whatever he’s done.

As an artist, what is your principal inspiration?

My principal inspiration, in the beginning, as a dancer, was Eric Bruhn and Nureyev. To me, they were the epitome of what classical dancing was all about. I was also lucky in The Australian Ballet because we had Ray Powell and Sir Robert Helpmann – and Algeranoff at one stage, too – all great character actors who could do amazing things on stage. The classical standard was set by the fact that we performed with Bruhn and Nureyev for two or three years and the value of our character work was set because we had these great artists with us. It’s wonderful to have the luck to do that and it’s a while since any of our dancers have had the luck to be around great character dancers and to see this sort of thing happening.

I’ve never believed that character work isn’t of value. I believe that if you’re telling a story ballet, then the most important thing is the story, not the dancing even though we use the dancing to tell the story. Because of this I’ve always been very comfortable in what I do.

Inspiration for roles comes from a variety of places. And these days you can get video of any bloody film in the entire world. The other day I went into a place which had more DVDs than I’ve seen in my life! There’s no reason why we can’t look up any actor; in my day, we had to remember them. We had to remember ballets. We hardly ever saw a dance company out here and if we did, that had to remain in your memory and, of course, memory enhances and makes you believe that they were doing it better than they were. Now we can just pick up a video and it’s so much easier.

In Graeme Murphy’s Nutcracker (created in 1992) you play one of the Russian émigré friends of the elderly Clara. Tell me about the process of that creation.

Well, it wasn’t only Graeme but Kristian Fredrikson, who designed it, who was also very active in the way the ballet was put together. In the first rehearsals, we also had all of those wonderful Borovansky dancers and other dancers from the early age, around us – Maggie Scott, Valrene Tweedie, Athol Willoughby, Harry Haythorne. In the ballet, the old dancers are part of the Russian émigré community, which was only small. So, every Christmas they would go to Clara’s place, bringing their little gifts and this year they knew that it would be her last Christmas because she was starting to fade. They’re all worried about her because she’s living alone, with her memories. And my goodness, when you reach my age, you understand those things. I’ve visited people and thought that might be the last time I visit them.

The range of those characters plus the fact that we (the cast) were so different in our own personalities and lifestyles, meant that we all came out so distinctly different: the part that Harry played, that Paul de Masson played, I think even Stephen Baynes was in the first one. We had all these different old men and you could see them as that. They’ve got the camaraderie of being expatriots and having a common interest in Clara. I found it very easy to start that character.

Graeme allowed us to have some input and that always makes tha character better because it fits you better. If you’ve got to walk into someone else’s shoes it takes you a while to work out what those shoes are like and how that person walked in those shoes. I pity anybody who’s trying to get into my roles because they are so personal, so based on my body and my way of moving.

When you did the group dance at the party in Nutcracker, how much instruction did you get from Graeme on how to do it?

A lot. Graeme was very determined about how it should happen, what the steps were and he kept encouraging us to do more. He was like a cook: he’d put in the ingredients but then as the ingredients either came up or down, he added a bit more salt or flour or whatever. It wasn’t ad libbed.

Did he make you go harder or slower?

He did. He would say to people, “I think this doesn’t work, I think this should happen.” I think that’s the way most theatre producers work these days. They do a reading of a play, then work out what these characters should be doing and whether it’s coming across and whether it’s readable to an audience. Graeme was the person doing that. But he had all the gimmicks of bringing out the photos, which makes the scene work so well. And the fact when she (Clara) was going to have a heartattack and the bit where she has too much vodka and dances, thinking she can do more than she actually can; and the lovely bit with the doctor coming in with the film.

How strenuous did you find it?

Not at all. Graeme has the greatest flow of ideas of anyone I’ve ever worked with. The man is so amazing, so amazing that I’ll give you a small anecdote. When I was Ballet Master here and he was doing an early ballet, he spent time on a lift with a girl that wasn’t working. He could get her up there and do things but it was not coming out the way he wanted and they weren’t getting it. He tried for about two days then the next day he said, “That’s not working, Colin.” And he not only cut that but about 32 bars going into it because that was part of the build-up and he started from scratch. I thought, why would you do that, I loved all that! But then two or three years later, it appears in another ballet. It’s mulled around, and he’s worked out how to get in and out of that lift so that it looks effective and it’s gone in somewhere else. I love this man, I mean, this is really great stuff. And it’s sensible, why waste all that time?

You are the only foundation member of The Australian Ballet who still performs with the company on a regular basis. What does the foreseeable future hold in this area?

Death! I think I’m very lucky at the moment in two ways: the company still uses me, and I think they like me, and there are not too many of my era who are willing to get up and make an idiot of themselves. I hope that as I go into my nth year, they’ll still continue to use me.

Many interpreters of character roles tend to have a speciality that distinguishes their approach, for example: the late Ray Powell was, at his best, a benevolent bumbler; The Royal Ballet’s Derek Rencher always maintains a dignified distance; Ken Whitmore camped it up. You completely defy categorization, which in ballet terms, at least, puts you in league with the likes of, say, a Geoffrey Rush, on screen. His output, for example, includes the comical entrepneur in Shakespeare in Love and the evil political figure in Elizabeth, to name two roles from the same historical period and about the same time in his acting career. How have you managed such variety?

Going back to movies, which you just brought up, the one type of actor I don’t like is the John Wayne. John Wayne was John Wayne in every movie he did. Why people said he was good, I have no idea. I don’t think that’s acting. I think acting is when you get somebody like Geoffrey Rush who tries to delve into the character and brings out what that character should be. And I think that’s fun, don’t you?

Yes, but to be able to do it?

Well, the one thing I don’t want to be on stage is Colin Peasley. I’ve never been tempted to be myself; I don’t like myself so much that I want to replicate myself all over the place. An important part of theatre is the preparation time: when you’re in your dressingroom. Martha Graham phrased it beautifully: as she was putting all this hot black on her eyelashes, she said, “When you look in the mirror, you don’t look back at yourself but Cytemnestra does!”and with that, she upped and out the door. That’s exactly what it’s all about. Going into the dressingroom and putting on rock music while you’re slapping on a little bit of face, isn’t preparing for a role at all. Preparing for a role is thinking about it and getting your face to look like you think that person should look. Then when you put on the costume you are that character, not in the Nijinsky way – they say he used to be in character for an hour after the performance, which I think is a bit overdone but I understand what he was doing. Look at those photos of Nijinsky – in every photo he looks different.

You just said you don’t want to be Colin Peasley. Tell us a little bit about Colin Peasley. I know you’re fussy about ironing, so you’re big on costume, even in everyday life; you like it just right…

I think Colin Peasley’s biggest regret in life is that he didn’t discover dance earlier. Although I was a ballroom dancer from the age of 16, I didn’t start doing classical dance until I was about 21. That was obviously too late to be a dancer, even in my day. I’ve had this huge love of dance ever since but not the capacity to fulfil it. That’s a regret in my life.

The joy in my life, is that when you come to a thing late in life, the love continues longer but also you come to it with more knowledge, more understanding of what you’re doing. It’s not monkey see, monkey do like it is with a five or six year-old kid, so, I think I’ve approached dance more intellectually, which is probably the wrong way to approach it. But, it’s meant that I’ve had a huge joy in teaching and I love teaching. It’s not just saying, “Point your foot here!” it’s trying to work out why you point your foot here. That’s a part of learning, asking more questions than you know the answers to. Colin Peasley loves all that.

And, he loves to be on stage. They could ask me to walk on as a butler and I’d say, “Yes, please!” I don’t have to be a star, I just like being there.

And why?

Because it’s a drug. The excitement of being on stage, the buzz of people around you, the old thing about the smell of grease paint and the roar of the crowd is all there. And at the end of a performance when they’re all yelling and screaming, even if you’re in the back row, you imagine it’s for you. Nobody stood in the back row thinking it’s all for Fonteyn and Nureyev but for them, because they did such a lovely peasant – and I do, too.

In recent years you’ve become very adept at handling computers and technology, partly in your work as Education Program Manager. You’re not just a performer, there’s a lot more to your life…

Yes and this is partly to do with my upbringing and the way my family approached education. They thought it was very important and I do, too. They allowed me to question and I’m a questioner, I want to know how things work. That’s the reason why I cook and I enjoy cooking. I’m a voracious reader, I’m a collector of books; I have more books in my house than I have house to put them in.

What sort?

I’m a very catholic reader, when I’m on planes I read detective stories, which can be the biggest load of trash and it’s relaxing not to have to think. But then, I would say I’ve got the largest collection of ballet books in Australia outside the Australian Ballet School. I’ve been collecting since I discovered ballet. All this has kept me with what I think is most important for life and that is an interest. I’ve got an interest and my basic interest is dance but now there is a lot of other things, too.

Tell me a little bit more about your family background?

I grew up in Sydney, I have a sister who is seven years younger than me, which meant that we were both treated as only children, which was a disaster. I’m not close to any of my relations. I went to Sydney Technical High School. At that stage, I imagined I wanted to be an architect. I studied German at school and that’s strange because this is just after the war (WWII) and they were still teaching it. I got my qualification certificate to go into university and I never went. We didn’t have the money and I couldn’t afford to do things like that so I worked in a shop during the day and I did some night school courses. Then ballroom came into my life, I rushed off to ballroom classes and became a teacher of ballroom.

When I was at Bodenwieser’s and doing ballroom, I had a very good friend, Alan, an Asian, who said to me that he wanted to do acrobatic dancing and I said I’d always wanted to do tap. We’d taken our girlfriends to the Tivoli for one Saturday evening – when you’re doing ballroom, your partners are always your girlfriends because you don’t want to loose them – it’s the truth! Even if you’re not really compatible, they’re your girlfriend. On the back of the program was an ad for the Tivoli acrobatic and tap school; it was like God talking to us. So we went to Tibor Rudas and Sugar Baba. And we tapped and acrobatted ourselves away there, while I was still doing ballroom and modern dance and working during the day. Across the way, we saw a jazz class that was absolutely wonderful. I said to Alan, we’ve got to join that class, thinking of Fred Astaire and all those people. The woman there said you’ve got to do one classical class to do one jazz class. I said, “No, thank you,” went back up and did shuffle, step, shuffle, step and kept looking. Eventually I went back, talking for both of us, “We will do it, on the understanding it’s a private lesson and we don’t have to wear tights.” So, we did our first classical ballet lesson – I was 21 – in shorts at ten o’clock at night with Valrene Tweedie. That’s how it all started.

What did your forebears do, what were some of their occupations?

My father was a printer and my mother was a housewife. My grandfather on my father’s side was a baker. I don’t know what my grandfather on my mother’s side did, but that’s where the German side of me comes in, their name was Waghorn.

I’m still intrigued by your ability with computers because it tends to be a generational thing. Everyone under 20 lives on the internet and computers are an integral part of their lives but many middle aged people and even some younger ones, whom I know, are completely lost with that technology, yet you’ve taken to it so easily…

I think this is part of my nature. I’ve got this dreadful streak that I must be self-sufficient. For instance, I must be able to sew up trousers on a machine, I must know how to bake a cake, wash a floor and do all those things. I live by myself, so I’m entirely self-sufficient. And if I’m going to work with one of these things (he indicates his computer), I want to know exactly how it works and how much I can do with it. That’s why I play the piano. I thought, if I’m going to be a dancer, and you read that all these great choreographers and dancers are always musicians, I thought I’ve got to learn music, too.

Do you still play, do you practise?

I play but I don’t practise. And I only play pop; I don’t play classical any more.

When you say “pop”, what do you mean?

I mean (bursting into song) “Daisy, daisy, give me your answer do.”

On that cheerful note, I think we will wrap it up. Thank you Colin.

My pleasure.

Blazenka Brysha

Futher information about Colin Peasley may be accessed via the National Library of Australia web sitewww.australiadancing.org

Dear Colin! What a wonderful interview! It is some 55 years since I danced with you (ballroom), but I have never forgotten you nor the pleasure it was to dance with you, and I have followed your career with interest ever since. My one regret is that I have never been able to see you perform except on TV nearly as many years ago. Happy days!

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment, Beverley. The breadth, depth and length – now spanning 50 years – of Colin’s ballet stage career is phenomenal. Although Colin has made his huge contribution through communicating without using words, I was keen to record what he had to say about his work as an artist and how he said it. I wanted to present Colin speaking for himself, which is why I used the question-answer format, so that it could stand as a primary source of material of historical value. The beauty of today’s technology is that it makes this both possible and then easily accessible. While seeing a live performance is the ultimate theatrical experience, film enables us to share something of that and certainly gives us a precious record of what is otherwise an ephemeral creation. Fortunately, there’s quite a bit of footage of Colin’s work in existence.

LikeLike

Interesting article. Do you know anything more about James Upshaw?

Thanks

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Laurie. Regrettably, I don’t know much more about James Upshaw than that he was a TV producer from the 1960s and 70s, who was also married to ballet dancer Valrene Tweedie (see obituary:

http://www.smh.com.au/news/obituaries/grand-dame-of-australian-dance/2008/08/06/1217702140711.html?page=2). I have tried googling his name, but only found references for some of his productions and nothing more.

LikeLike