The Dream/Marguerite and Armand

The Australian Ballet

Livestream/Live on Ballet TV

21 Nov–5 Dec 2023

Reviewed by Blazenka Brysha

The Australian Ballet’s current livestream Ashton programme Marguerite and Armand followed by The Dream, features an interview with guest conductor Barry Wordsworth in which the maestro pays tribute to Dudley Simpson for his version of the score using the Liszt B minor piano sonata for Marguerite and Armand.

He says, ‘This is an extraordinary history because the version that everyone will hear this evening is actually the third version that was made of the score. When Sir Fred first did it, he was persuaded…not to have the piano, just to have the orchestra, and Humphrey Searle, who was a very avant garde composer at the time, wrote a version for orchestra. It was deemed after a while that it didn’t work. So then Gordon Jacob did a second version, which had a little bit of piano, but then finally, what excites me the most, is that Dudley Simpson, who was an Australian conductor, worked here for the Borovansky company and had gone to London as assiatant conductor for the Royal Opera House, conducting for Fonteyn, they asked him to do it and he said, “Yes I will, but every pianist plays the List Sonata, so, I’m going to leave the Liszt untampered and just add the orchestra, to bolster things up, to make it even more theatrical than the original version.” And it’s the most wonderful version, it really does the job.’

Barry Wordsworth, who is Principal Guest Conductor of The Royal Ballet, has a long-standing international career and is no stranger to The Australian Ballet. It is significant that he puts the spotlight on Dudley Simpson, mentioning his beginnings. Dudley Simpson started with the Borovansky Ballet in the mid-1940s as pianist and rose to positions of conductor and finally musical director in 1957. Coincidentally, that was the year Margo Fonteyn was guest artist of the Borovansky Ballet. Simpson’s ballet work was hallmarked by great sensitivity to the needs of dancers and the demands of music, making him extremely popular with dancers, including Fonteyn. She never warmed to Borovansky but loved the company’s artists and happily returned to guest with The Australian Ballet in its early days when Borovansky personnel contributed to more than half of the young company’s artists, including all the Australian principals, the musical and technical directors. Even Peggy Van Praagh, the founding artistic director of The Australian Ballet, first came to Australia to direct the Borovansky Ballet after Borovansky died. The Borovansky Ballet also built the audience without which The Australian Ballet could not have been formed.

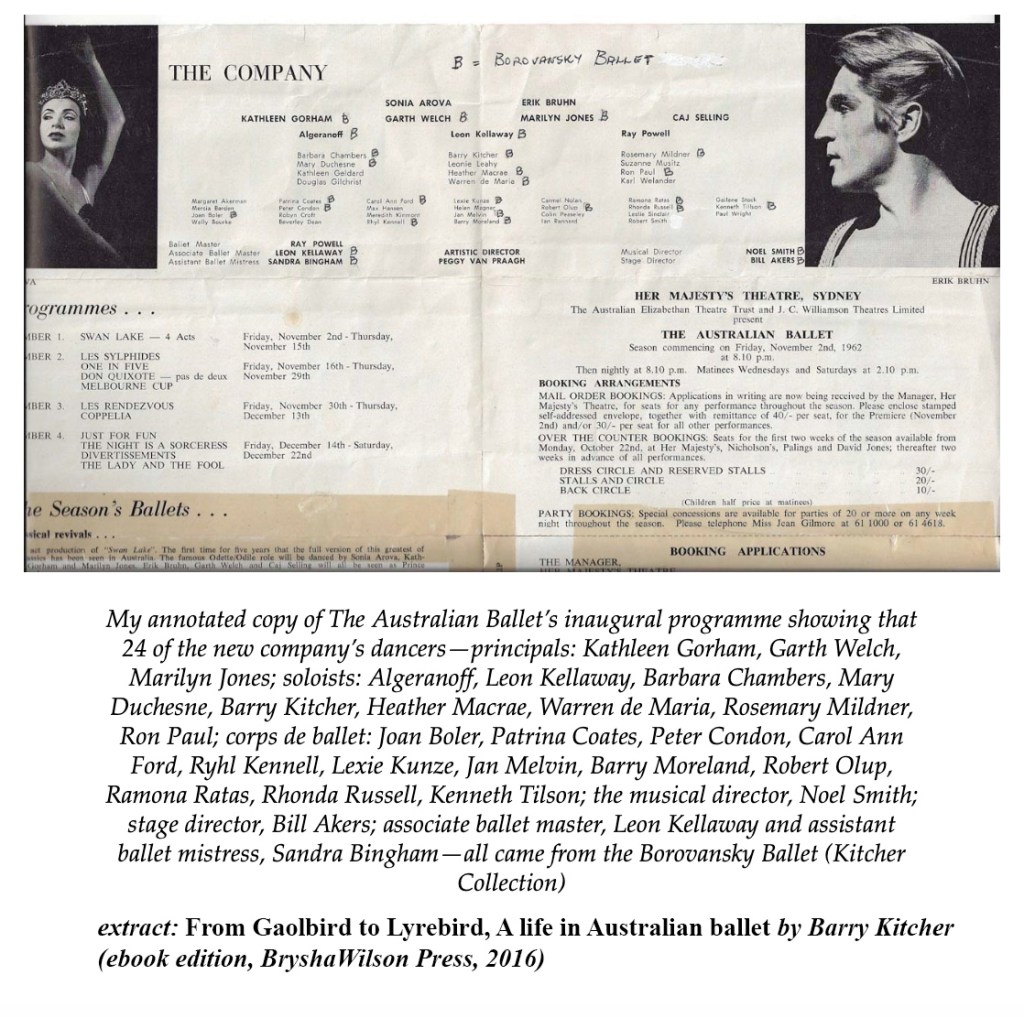

The Borovansky Ballet’s central contribution to the formation of The Australian Ballet seemed to have been forgotten over the years, causing concern particularly among former Borovansky Ballet personnel. This proved a major catalyst for Borovansky and TAB alumnus Barry Kitcher to write his memoir From Gaolbird to Lyrebird, a life in Australian ballet (Front Page, 2001). When it was re-issued an ebook, Kitcher included a copy of The Australian Ballet’s 1962 promotional flyer on which he had annotated all the names of Borovansky personnel with a ‘B’. It is reproduced below.

The Australian Ballet’s first Musical Director Noel Smith had been assistant conductor when Dudley Simpson was Borovansky’s musical director. These days Dudley Simpson is best known for his ingenious incidental music for the most highly regarded episodes of the (now cult) TV series Dr Who.

Ballet is an art passed from body to body and built on the foundation of connecting and intersecting strands of history. Provenance is extremely important.

In the livestream interview Barry Wordsworth, who likewise has a deep affinity with dance, acknowledges his own mentor The Royal Ballet’s John Lanchbery, who arranged and orchestrated the music for many Ashton ballets including The Dream. Lanchbery, too, had strong links with The Australian Ballet, even as resident musical director in the 1970s. Wordsworth also taps into the connection between Frederick Ashton and The Royal Ballet and the relationship between them and The Australian Ballet (TAB). The links are close and strong.

In his introductory remarks, Artistic Director David Hallberg mentions that one of the Ashton ballets in this programme has been in the company’s repertoire a long time and that the other is new. Later he refers to Marguerite and Armand as being an Australian premiere. Actually it is only a premiere for the company because the Australian premiere was by the Royal Ballet on its 2002 Australian tour. In fact, Sylvie Guillem, who danced Marguerite on that 2002 tour, coached the company for the current staging. Hallberg probably means that it is The Australian Ballet premiere but the incorrect wording is also repeated in a promotional video on the company’s website and these things have a way of living on line for a long time so they are worth clearing up.

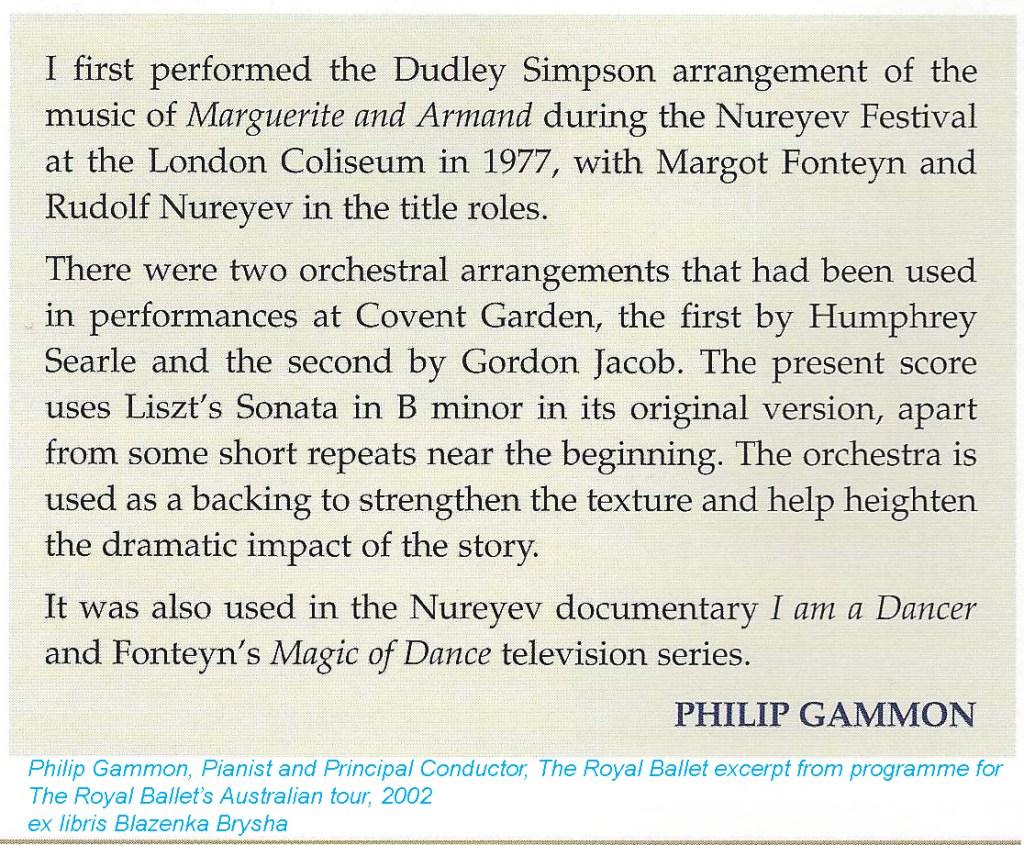

Below is an excerpt from The Royal Ballet’s 2002 Australian tour programme notes on the music used for Marguerite and Armand:

As for the current livestream programme by TAB, the major issue is the vast difference in quality between the choreography for Marguerite and Armand, and for The Dream. The former is a minor work, devised as a vehicle for the partnership of Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev at the peak of its stellar trajectory. By comparison, The Dream, created to show a deeply accomplished large ballet company, is like a Bach concerto compared to a simple tune however beguiling depending on the singer.

The major problem with Marguerite and Armand is that the ballet is indelibly associated with Fonteyn and Nureyev. Because it was filmed several times, it can still be seen in bits, at the very least, on YouTube. The work depended on the combined magnetism of the two stars as they throw themselves into it as if jumping of a bridge together while having sex. They are not shy about it, so why should we be? But there’s a whole lot more to it and that’s the inherent emotional drama of a forbidden enrapturing love torn asunder. In Fonteyn, Nureyev had met his match, a consummate artist of complete dedication to the practice of the art. It may be hard for other dancers to match them in these roles and that’s the way it has seemed.

The current livestream featuring Principal Amy Harris, (regrettably retired as of last Saturday 25.11.2023), and Senior Artist Nathan Brook in the title roles, has prompted a rethink for me. Together with the commanding presence of Steven Heathcote, guesting as the Father, they ejected enough drama into the work to push the slight and repetitive choreography under the chaise longue, the ballet’s key prop. Heathcote, now on the company’s ballet staff, is TAB’s most accomplished principal of the last 30 years at least. In this ballet he is not taxed with any ballet move: he walks, he interacts physically, he acts. And therein lies the secret of success.

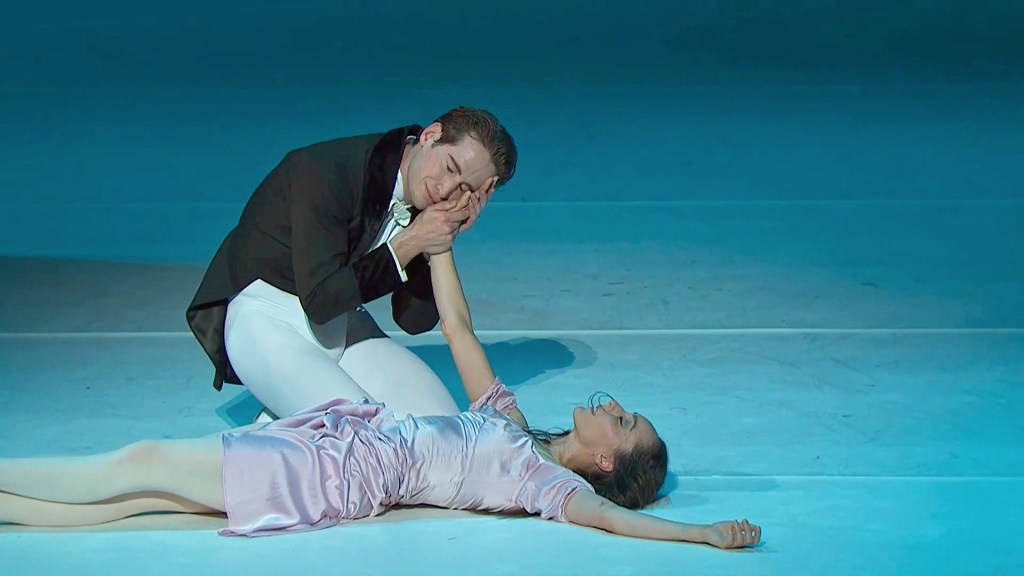

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

Meanwhile, Brook was a revelation in his portrayal of Armand. In dance terms, he went big on the moves across the stage, which was a good choice because he was expected to cover more ground than the MCG. The power he harnesses made him a presence to be reckoned with. It certainly gets Marguerite’s eager attention and they connect. That’s a great deal more than Sylvie Guillem and Jonathan Cope did in the Royal Ballet’s 2002 Australian premiere of the work. For all their considerable individual star quality they couldn’t make it override the choreography’s limitations. So, it is particularly heartening to watch an artist like Nathan Brook own a role like Armand and push it beyond the limitations of its choreographic boundaries. This, too, was a classic Nureyev tactic but the trick is that every dancer must own it individually to make it work. Harris matched him with every response and an impetus all her own. She was magnificent with Heathcote.

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

Harris and Brook seize the ballet’s dramatic potential and that carries it, except during some of the big lifts that demand Marguerite be tossed about at head height, which breaks the connection between lovers. Those lifts do not enhance or progress the drama. Fonteyn and Nureyev overcame these impediments by never losing the sense of intimate contact. Nureyev ensured it by his knack for not taking his eyes off Fonteyn, no matter how he had to manipulate her form. Meanwhile, she worked with him, steeling her body to facilitate lifts and softening it to a pliable limpness for the softer entwinings.

The essence of this choreography is not about the movement but how you use it to tell the story. Heathcote, as the Father, uses stillness and subtle shifts of the neck to signify his character’s realisation of the crushing magnitude of the emotions at stake as Marguerite acquiesces to his request that she give up her love for Armand. It sets the momentum for the unraveling of the tragic drama as Armand picks up the thread with his abusive and scornful treatment of Marguerite. Brook makes Armand’s wounded feelings very clear by his taut deportment and angry face, then follows up with a burst of menacingly powerful dancing. Harris matches his anger with her distress. From there the passions play out swiftly, culminating in Marguerite’s death.

Marguerite and Armand is actually a work inviting new and original interpretations. There can be as many uniquely original Marguerites and Armands as there are dancers prepared to enter the potential depths of this story. Furthermore, TAB has a strong history of using older retired dancers as guest artists in roles for senior characters in the ballets and it would be good to see more of that whenever possible, both as a gift to the audience and an inspiration for the company.

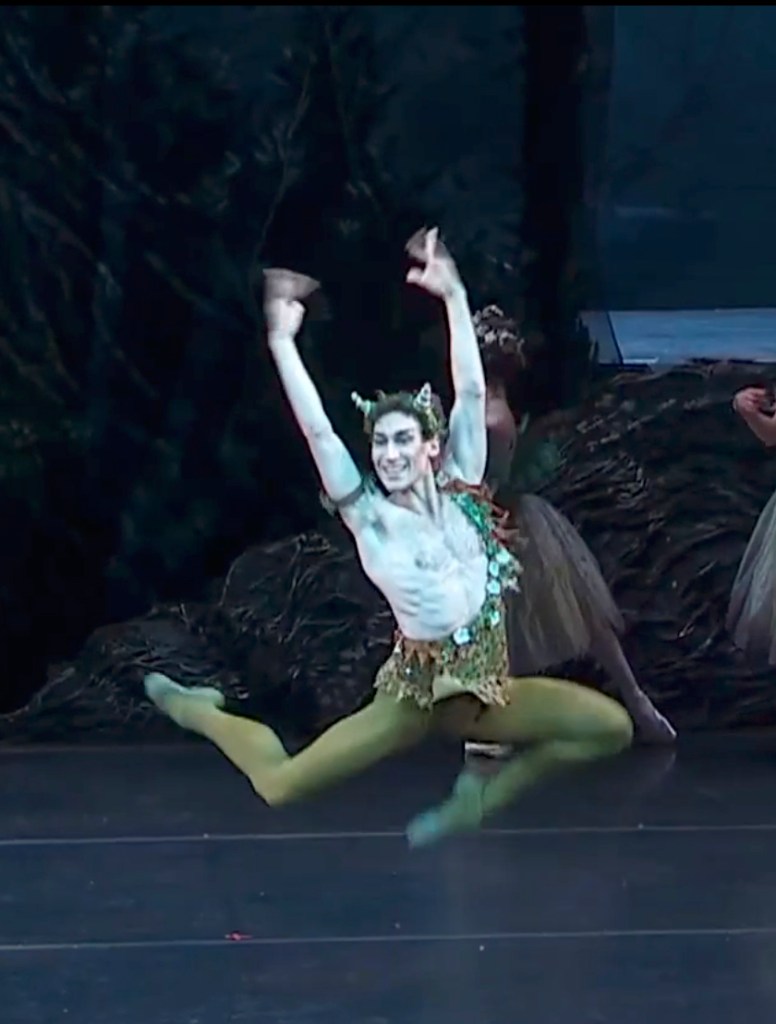

The Dream (mus. Mendelssohn, arr. Lanchbery) has been in the company’s repertoire since 1969. Ashton’s magical retelling of the storyline of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is ideally suited to TAB because it was created to show off a range of talent in a large company. The livestream performance was a sparkling affair, with light and lovely fairies flitting about, swarming and scattering. The unintentional untidiness at times gave it a surreally contemporary look, not exactly Ashton and indicative of just how hard it can be to meet the exacting requirements of Ashton’s intricacies.

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The roles of queen and king of the fairies are not overly demanding of interpretive abilities and Ako Kondo as Titania was suitably imperative and Chengwu Guo dismissively arrogant. Bret Chynoweth was a mercurial and delightfully impish Puck and Luke Marchant a skittish Bottom who becomes a charming donkey. The rest of the Rustics were a lively bunch of yokels, integral to the plot as a foil to the otherworldliness of the fairies and as a key component of the narrative. The mix ups between the four human lovers who have stumbled into the enchanted forest are intentionally confusing and keeping up with the action is fast paced for the dancers—Rina Nemoto as Hermia, Hugo Dumapit as Lysander, Valerie Tereshchenko as Helena and Mason Lovegrove as Demitrius. I gave up trying to follow it despite the colour coded costumes and just enjoyed the antics.

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

Ashton was a firm believer in comic subtlety but Shakespeare liked to play it for laughs so there’s a mismatch beyond the abstract notion that Ashton is a master choreographer and Shakespeare a master wordsmith, two domains that cannot be translated into each other. That is precisely what makes dance, and the art ballet in particular, so important—its ability to say things that words cannot. Nevertheless, The Dream is a beautiful ballet and a feel-good work that ends a programme on a pleasing note.

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

TAB’s relatively recent inclusion of livestream has come a long way in a few years. In earlier days, presenter questions and material were not as well prepared as now. The interviewees were largely self-conscious and either uncomfortably guarded or unable to give answers that did justice to the event. That has changed as the artistic and ancillary staff plays more of a role and the dancers have learned to be more themselves as highly trained artists with insights to offer audiences.

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

The Australian Ballet Livestream 21.11–5.12.23

Initially, it was a case of listening to the ancillary material just in case there was something that might otherwise be missed. Now it constitutes an important element of the programme, also featuring items filmed for the company’s Ballet TV promotional material. You can fast forward through all this but if you did, you would be short changing yourself. Hallberg’s focus on championing the dancers is reaping results and hearing their take on things is a highlight.

Among all the other valuable material lacing this current livestream, there is some very informative discussion of male dancing en pointe as required for the character of Bottom, in The Dream, when he is transformed into a donkey. We hear from dancers and the rehab physiotherapist.

Livestream is not cheap to produce and TAB has been relying on the government, corporations and philanthropy to make it happen. An uptake on subscriptions to the service is to be hoped for.

Livestream now makes the national ballet company nationally available because it overcomes the constraints of economics, geography and other physical limitations that prevent the company from touring further afield and audiences from attending its programmes in person. Livestream is the next best thing, and to be recommended highly.

This livestream runs to 5 December. Tickets are available via The Australian Ballet ticket website and cost $29.