Without Jean Stewart’s photography a major portion of the history of the development of classical ballet in Australia would have been lost. Her speciality was live performance and her photographs are a tantalising glimpse of living dance in action.

Jean Stewart (1921–2017) was one of three photographers who between them have left a massive photographic archive thanks to their interest in both photography and ballet. While Hugh P Hall (1899–1967) concentrated most memorably on the big picture, especially evident in the vast number of his 1930s Ballets Russes tours photos, and Walter Stringer (1907–2001) mostly responded to the aesthetics of ballet’s traditional side, Stewart was drawn to character and action. Hall was already aiming his camera at Anna Pavlova in the 1920s and was still working when Stringer and Stewart got going in the 1940s, then Stringer continued to work into the later 20th century.

Given the ephemeral nature of dance, the photographic collections of these three pioneers give us a precious record and Stewart’s work shines as its central component.

If only one photograph was allowed to survive as a testament to mid-century Australian ballet, it would have to be Jean Stewart’s capture of Martin Rubinstein as Harlequin (Carnaval, Ballet Guild, 1949)—airborne, magnificent, a vision of joy in flight. The dancer hangs weightless in mid-air, behind him, a rudimentary set.

It tells the story of how aesthetic aspirations aligned with a grand tradition found their expression in energetic enthusiasm sustained by shoestring budgets. But that’s not all because this picture comes bursting at the seams with a big back-story: the story of mid-century Australian ballet and Jean Stewart was there, photographically documenting big chunks of it.

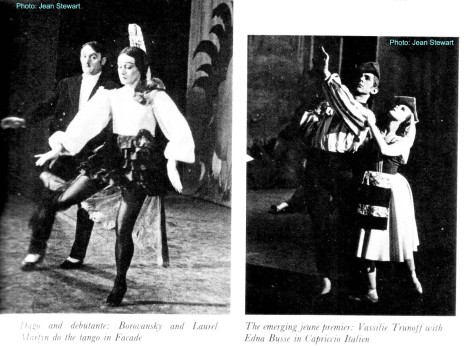

In the 1940s Stewart developed her art under Edouard Borovansky’s watchful eye, snapping ballet as the audiences saw it, recording the doings on the stage. Her photographs of the historic 1947–1949 Ballet Rambert tour are a unique record of an event that had a major impact on the subsequent evolution of Australian ballet. From the later 1940s and well into the 1950s she worked closely with Laurel Martyn who directed the Ballet Guild (later Victorian Ballet Guild) after parting with Borovansky.

Jean Stewart’s photographs grace all the important books that deal with or touch on ballet performance in Australia during the 1940s and ’50s: Ballet in Australia, the Second Act, 1940–1980, Edward H. Pask (Oxford University Press, 1982), Opera and Ballet in Australia, John Cargher (Cassell Australia, 1977), My Journey Through Dance, Charles Lisner, (University of Queensland Press, 1979), Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet, Frank Salter (Wildcat Press, Sydney,1980), From Gaolbird to Lyrebird—a life in Australian ballet, Barry Kitcher (Front Page, Melbourne, 2001; new eBook edition BryshaWilson Press, 2016), Australia Dances—Creating Australian dance 1945–1965, Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon (Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2010) and Dame Maggie Scott—A Life in Dance, Michelle Potter (Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2014).

They can also be found in many collections, some still in private hands and others now in public and institutional libraries, most notably the State Library of Victoria (SLV) to which Stewart donated her entire collection in recent years. Though Stewart’s work is well known, her extraordinary achievement has never received the recognition it deserves.

It was a serendipitous mix of contributing factors that resulted in Stewart’s historically important photographic output. Speaking of how it all started, she stressed, ‘As a girl I had cameras. Photography was the passion.’ Her family’s devotion to the works of Gilbert and Sullivan and their consequent connection with theatre gave her both subject matter for her photography and access to it. Work with ballet only came later.

Jean Stewart was born in 1921, in Melbourne, to a theatre-loving family that was especially fond of Gilbert and Sullivan. Her maternal grandfather was a conductor in private performances and held Gilbert and Sullivan musical soirées sending out invitation cards with the instructions: ‘Carriages at 10.30’. Stewart found this very amusing as a relic from another era, saying dismissively, ‘That was before my mother was born.’ As for Gilbert and Sullivan, she said, ‘It was the entertainment of the day and I was lucky that my family brought me up to love Gilbert and Sullivan.’ Among the material she donated to the SLV were three books of Gilbert and Sullivan piano scores copiously annotated by her grandfather for the soirée performances he gave. More importantly, it included the extensive collection of her Gilbert and Sullivan photos of the performances staged by J. C. Williamson, Australia’s premier theatrical entrepreneurs in the 20th century and holders of the performance rights for Gilbert and Sullivan in Australia.

‘I went to all the Gilbert and Sullivan and photographed everything,’ she said emphatically.

It so happened that Stewart’s grandfather knew musician Claude Kingston who became her parents’ friend and general manager of J. C. Williamson’s theatrical business based at His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne. It was Kingston who gave Stewart permission to photograph the Gilbert and Sullivan performances.

Much transpired between the time that the girl with the cameras became the photographer of professional live theatre. Young Jean attended St Catherine’s School, one of Melbourne’s exclusive schools for girls and it was there that her bent for photography took a turn towards the professional level. She explained, ‘I had to earn a living and a teacher at school suggested I do radiography.’

So, on leaving school Stewart worked during the day at the old Royal Melbourne Hospital and studied at night at RMIT for two years. Speaking of that experience, Stewart said, ‘There was only one other woman in the course. Women weren’t welcome in radiography. It was male chauvinism—women were nurses and typists. Wouldn’t they be rolling in their graves if they could see computers today!’

Stewart won a prize for Radiography and received two guineas from the radiologist doctors. After qualifying, Stewart worked in private practice in Collins Street but was not happy there so she changed jobs to the Heidelberg Rehabilitation Hospital where she remained until her retirement in 1986. When she was donating her photographic collection to the SLV, she also gave her collection of historic xray film to the Australian Society of Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy.

Stewart’s mother gave her a Kodak Recomar 33 camera as a gift on graduating from her radiography course. Apart from the comprehensive technical understanding of photographic processes that Stewart would have gained from qualifying as a radiographer, she also studied photography at RMIT. It was the Recomar that Stewart would use exclusively out front in the theatres but she also used a 35 mm camera backstage.

Stewart’s friendship with Avona James, a dancer in Borovansky’s fledgling company in the early 1940s was her introduction to the world of ballet. ‘I went and watched her dancing,’ said Stewart. ‘I bought tickets and got involved.’ As she was already photographing Gilbert and Sullivan at His Majesty’s Theatre, taking photos of Borovansky performances, which were held there (as well as at the Borovansky studio at Roma House, 238 Elizabeth St, Melbourne), was a natural extension of her work, especially since dance is such a strongly visual art.

It so happened that Stewart got on well with dancers. Valda Jack (now Mrs Valda Lang) who was in the company in the 1940s said, ‘Jean was part of the scenery, she was always there, in the wings, out front, taking photos. Both our middle names were Margaret and she’d say, how are you, Valda Margaret? and I’d say, very well, Jean Margaret!’

After printing her photographs, Stewart would take them to the dancers who vetted the photos. Stewart said, ‘If a hand or foot did not pass muster (in ballet criteria for what is acceptable), out it went. The dancers would say, Don’t let Boro see that.’ And so, what Boro saw, Boro liked, which gave Stewart carte blanche around the company and even Borovansky himself as a performer. In fact, of the photos she took, Stewart’s all-time favourite is the photograph of Borovansky as Pierrot in Le Carnaval when he has just failed to net the Butterfly with his hat. ‘It’s the look on his face,’ said Stewart in explaining her choice.

Jean Stewart’s personal favourite of all the photos she took. ‘It’s the look on his face,’ she said.

Stewart got on very well on a personal level with Borovansky, who even told her to wear trousers to make it easier for her to go up lighting stands and generally get around in doing her photography. The trousers must have made things easier in other ways as well because Stewart lugged her photographic gear about on trams. ‘Unipod between my legs, camera against my bosom,’ is how she described sitting in the tram.

Stewart attributed various of the connections she made with theatre to tram travel, including knowing actor director Irene Mitchell, under whom Melbourne’s Little Theatre spawned several generations of Australian theatre artists. Said Stewart, ‘Everybody knew everybody then, we travelled on trams together.’

It was Mitchell who introduced Stewart to theatrical entrepreneur Garnet Carroll who was a partner in the leasehold on the Princess Theatre. After Stewart showed him some of her Borovansky photographs, he gave her permission to photograph the Princess stage.

‘Everything was laid-back then,’ said Stewart of her experience of working in theatres. Eventually, Stewart also gained permission to photograph live performance at the Palais Theatre and the Union Theatre at both of which the Ballet Guild appeared. ‘Only (Walter) Stringer also had permission to photograph all four stages live,’ she stressed. Permission to photograph was one thing, entry to the theatres another. ‘I paid for all my seats,’ Stewart pointed out proudly, signalling her independence and freedom from any kind of compromising obligation to vested interests.

Wearing trousers, in an era when it was not an acceptable form of everyday dress for women, made Jean Stewart’s work much easier, not just as a photographer but also as stage manager for Ballet Guild.

Photographing live theatre is one of the most difficult and technically challenging areas of photography and photographing dance is definitely the most demanding within that. Issues to do with light control and the mercurial movement of the performers are just the most obvious of the many daunting complexities facing the live ballet photographer. Apart from technical ability with a camera (complex enough with digital cameras, let alone with cameras of the era in which Stewart worked), the ballet photographer must also have both an eye for theatre and for movement. Having an eye for movement is like having an ear for music: you need to be able to feel the movement sympathetically, to understand what it is doing and why. Sometimes the content of that may be in the grand sweep of the whole and sometimes in the minutiae of detail. Every aspect of this is contained in Stewart’s photo of Rubinstein pausing gravity as Harlequin. It is also on magnificent display in Stewart’s capture of Rubinstein in his glorious death-leap as the Golden Slave in Schéhérazade, a moment that always brought the house down, according to Valda Jack, who danced as one of the concubines in the Borovansky Ballet’s premier season of the work (1946).

In Stewart’s photograph the Golden Slave has just plunged to the floor headfirst, landing on his neck, his body balanced vertically on his left shoulder and its weight supported by his left cheek and his right hand. Stewart remembered how when that photo was taken, Rubinstein rushed up to her as soon as he came off stage, asking, ‘Did you get it? I held it for you.’

Both this and the Harlequin photo are among the 11 Stewart photographs that are used without photo credit in Frank Salter’s Borovansky, the man who made Australian ballet. While Stewart was unbelievably generous with her photographs, unstintingly allowing their reproduction at every request and without payment, she did expect a photo credit, which unlike the authors of all the other books mentioned above, Salter did not give although he mentions her name among all the people he thanks in his general acknowledgements. Thirty-five years after the book’s publication, Stewart was quick to point out which of the photos used were hers.

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photos on p 109 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photos on p 142 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photos on p 143 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter. An autographed print of the Serge Bousloff in costume shot exists at the National Library of Australia credited as “Ritter-Jepessen Studios” but that is a copy. Stewart was adamant that this photo was hers and recorded the fact in her own copy of Salter’s book, now in the possession of Dawn Kelly, a Melbourne balletomane.

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photos on p 156 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photos on p 157 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter

Jean Stewart’s uncredited photo on p 171 of Borovansky: the man who made Australian ballet by Frank Salter

It was fortunate that Stewart had been introduced to Garnet Carroll and obtained permission to photograph the Princess Theatre stage because it was there that Ballet Rambert started its Australian tour. While it is the range of Stewart’s Rambert photographs—which includes tableaux of scenes in ballets, selected parts of on-stage action and portrait-style singling out of individual dancers— that makes them so valuable historically, it is her iconic captures of Sally Gilmour in Andrée Howard’s Lady into Fox and The Sailor’s Return that have passed on to posterity something of the impact that the Rambert visit had on the Australian dance consciousness. Here was a company bringing new and different works performed in ways not seen here before, yet all in a balletic context and, indeed, presented, along side a sprinkling of familiar traditional offerings, in major theatres. Also among the new works were ballets by Antony Tudor, including Jardin aux Lilas and Dark Elegies, which demanded that content be conveyed purely through movement: the movement had to carry the message/import, an approach that put quite new demands on both the choreographer and the dancers. Andrée Howard was also breaking new ground not just by being a woman, which still remains a rarity in ballet choreography, but also by devising ballets that challenged commonly held prejudices about sex and race, issues that remain topical even today.

Howard’s ballets are lost, Stewart’s photos remain. They can be found in collections both here and in London at the Rambert archive to which Stewart also generously donated relevant holdings. In Lady into Fox a young wife transforms into a fox and longs for the freedom of the wild into which her loving husband releases her despite his fearful awareness of an impending foxhunt. Sally Gilmour’s acclaimed portrayal of the transformation from woman to fox was regarded in its day as the reason for the ballet’s great popularity.

It is Stewart’s photo of Gilmour as the fox, seated upright and watchfully alert on a drawing room floor that Rambert artistic director Mark Baldwin used in Long forgotten images of Rambert and the birth of modern dance—in pictures an article in The Guardian (23.5.2013). Stewart’s other well-known photo relating to this work, a portrait of Gilmour posing as the Fox, shows not only the personification of the creature but also the fine detail of the terry towelling costume that effected the startling transformation.

Jean Stewart’s photo showing the terry towelling fabric of the fox costume that aided in the illusion of transformation in Gilmour’s performance.

Costume was also a critical element of The Sailor’s Return in which Gilmour portrayed the West Indies princess Tulip who is entrapped in a tragic destiny by racial prejudice against her. Again, Gilmour’s powerful performance came to the fore as a major contributing factor to the work’s popularity and artistic success. Stewart made a point of showing the character in her photographs, which give us both the joyous bride in her white finery and the concerned mother, in an apron and bare feet, tending the infant child in her arms. Full stage shots, taken from the dress circle, clearly show Tulip’s segregated position and the villagers’ rejection of her.

Scene from The Sailor’s Return, Ballet Rambert, 1948, showing Tulip’s segregation from the villagers.

It is not surprising that Stewart was drawn to these works by Howard, which showed the plight of women in an oppressive world. She herself was staunchly independent, even once declaring to me, ‘I don’t like marriage. I want to do what I want to do.’

The world of dance was a milieu that was overwhelmingly populated by women and, as Jean learned, you could even get the chance to wear the pants: literally in her case and metaphorically in the case of women like Rambert, de Valois and (in Australia) Kirsova, all of whom headed dance companies. So, when Laurel Martyn parted ways with Borovansky, in 1946, to lead the Ballet Guild, Stewart not only followed her but took on an official role. ‘I went up to Laurel and asked to be her stage manager.’

While Stewart continued to take some photos of the Borovansky Ballet after this, most notably of the studio performances of Black Swan in 1949, from 1950 she only photographed the Ballet Guild. Considering that the Ballet Guild was such an innovative yet low-key player of that era, Stewart’s photographs are all the more important as a major component of that company’s history, which remains a jigsaw whose pieces are all still to be found, let alone put together.

In a way, the parting with Borovansky represented a rupture.

‘Everything was very sectioned in those days,’ is how Stewart describes the era that we can say, with the hindsight of history and much water under the grievance bridge, was riddled with enmity and conflict and propaganda wars.

The artistically admired Kirsova Ballet (1941–1944) had the distinction of being called Australia’s first professional ballet company because the dancers were paid award wages but this was only during seasons, which left the dancers unemployed for considerable lengths of time. The Borovansky Ballet (1939–1961) clocked up the miles as Australia’s longest running professional ballet company (1944–1961, with periods of recess) prior to government funding. The National Theatre Ballet (1949–1955) was the grandest and slickest full-size operation presenting ballet on a scale and with a finish that had Brovansky alarmed but correctly convinced that it was unsustainable given the commercial realities of a vast land with a tiny population and a financial climate in which government funding didn’t exist. And then there was the Ballet Guild (1946–1959, evolving further under several name changes to 1976), working away quietly, appearing in nightclubs, between films at the Palais Theatre and on smaller stages such as the Union Theatre at Melbourne University and the small theatre at its own studio (St Patrick’s Hall, 470 Bourke Street). It earned much kudos for insisting on creating new works though like all the others it also did a smattering of traditional audience favourites such as Giselle and Coppélia.

Ballet Guild dancers performing an original ballet by director Laurel Martyn. Martin Rubinstein, centre front, appearing as a guest; along from him in the second row, head circled by very faint biro, is Valda Jack.

To give an example of the underhanded doings of that era, Stewart told a story involving the ballet Coppélia: ‘Boro took Eve King and Graham Smith two nights before the end of season. Martyn danced Franz. I have pictures of Laurel dressed as a man!’

That incident was in 1951 just as Borovansky was assembling his Jubilee Borovansky Ballet. More than 60 years later, Stewart still felt the sting of these conflicts, so much so that she declared Michelle Potter’s Dame Maggie Scott ‘The best (Australian) ballet history ever written. It was ecumenical. Other people wrote books but they were all sectioned.’

Stewart’s close connection with Ballet Guild resulted in extensive photographic documentation of that company’s work. It can only be hoped that the SLV will eventually upload the whole collection on line and bring to light an aspect of Australian ballet history that is all but forgotten these days.

By her own admission Stewart stopped photographing the stage in 1967, coincidentally the same year as the Guild—which became the Victorian Ballet Guild in 1959, then Victorian Ballet Company in 1963—morphed into Ballet Victoria. Nevertheless, she maintained a keen interest in ballet as a supporter and an audience member. She even continued to photograph at social events involving dance and dance people. For this she used a modern 35 mm camera and colour film.

The only substantial recognition Stewart received in her lifetime was from the Borovansky Ballet veterans who included her as one of themselves even at their most exclusive reunions. She was very proud of her photographic output and delighted in discussing and sharing it. Donating it to the SLV was a natural extension of her generosity and it made her very happy to know that her work was being put on line.

The one thing that bothered her were claims in a post about her work on the SLV site that she ‘would calculate the camera settings prior to the show by sitting in on rehearsals and then shoot the live performance with the pre-existing camera settings’ and that she used techniques of ‘dodging and printing-in (also known as burning-in)’.

‘There was no pre-setting, no dodging and no burning-in!’ she maintained adamantly to me and others. In fact, she requested a correction but none has been made to date.

In her continuing connection with ballet, Jean Stewart was an extremely generous financial supporter of among others, the Australian Ballet School and the Australian Institute of Classical Dance Dance Creation choreographic events. In fact, although she and her support for ballet were well known in ballet circles, many did not realise that she was one and the same as the photographer who took the historic ballet photos.

In some ways Jean Stewart photographer and Jean Stewart the person were two different personas. The photographer was self-effacing, busy with her camera on the sidelines, in the shadows, sharp-eyed and working quietly, capturing her subjects. You would not be aware of her but then you’d get a picture in the mail with your name on the back and Jean’s sticker with it. Her collection of these happy snaps is still in the hands of friends and still to be sorted into archival order but it also contains letters of thanks from the likes of Ballets Russes ballerina Irina Baronova.

Jean Stewart the private person was opinionated, feisty and gregarious. With her technical background, she was both a practical and competent woman who largely dispensed with tradesmen, confident that she could do the job better herself. She was particularly good at plumbing and even built a new room onto her holiday house.

In the very last years of her life, Jean lived in a retirement home and while her advanced years brought inevitable physical limitations, she retained a very sharp mind.

She was very helpful when I was putting together the new eBook edition of her good friend and Borovansky veteran Barry Kitcher’s memoir From Gaolbird to Lyrebird (BryshaWilson Press, 2016), which included many of her photographs and even a photo of her at the most recent Borovansky reunion.

Jean Stewart at the 1994 Borovansky Ballet Reunion, with Laurie Carew*. Photograph taken with Jean’s camera by unknown photographer. Photo courtesy of Barry Kitcher.

L–R Jean Stewart, Valda Jack and Valda Westerland at the 2015 Borovansky Ballet Reunion. Photo by Cheryl Kaloger, courtesy of Jan Melvin, included in the eBook edition of Gaolbird to Lyrebird by Barry Kitcher (BryshaWilson Press, 2016).

After one of our discussions about Borovansky she rang to say that she had found her newspaper cutting relating to the auction of Borovansky’s house at 14 Grandview Grove, Hawthorn, which she had attended. She didn’t know why she kept the cutting but told me that Borovansky had what was once called a ‘tennis block’, that is a double house block. When I suggested the property would be worth a fortune, considering that it was among the most prestigious ones in Melbourne’s ‘old money’ belt, she replied, ‘I don’t think he was stupid about money.’ A succession of phone calls followed as Jean went to the office of the home and got one of the staff to email me a copy of the cutting. Although she never mastered a digital camera or any of the current computer technology, she was very good at getting assistance on the digital front.

Just a week before she died, she gave Barry Kitcher a big piece of her mind, warning him to never use her mobile phone service provider with whom she was strongly dissatisfied.

Even though Jean had been retired for over 30 years from her career as a radiographer, surviving workmates were among the many people at her funeral, which was held at St John’s Anglican Church, Toorak because of long family connections with the church, although Jean was an avowed atheist. The poem her colleagues composed in honour of her retirement was reproduced on a commemorative card for the occasion. Entitled To One Who Cares, it began with the lines: Here’s to our Jean Stewart,/Who’s loved by one and all/When one needed help /All you had to do was call.

The announcement of the funeral details came with the instructions: no black, no flowers. Many of those who attended wore a dash of colour or a flash of sparkle in Jean’s honour. She loved colour and theatre and movement. As St John’s is one of today’s pet friendly churches, a contingent of canines also made an appearance because Jean was very fond of dogs and well known at the local dog park.

The dogs and their owners flanked the centre aisle, forming a guard of honour for Jean’s casket as it passed out of the church to the overture to Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience and a standing ovation from the congregation. As the stirring music played on, Barry Kitcher whispered, ‘That was used in (the ballet) Pineapple Poll**.’ And so it was Gilbert and Sullivan and ballet to the very end.

Vale Jean Stewart.

Blazenka Brysha

Jean Stewart with Judy Leech and dance critic Robin Grove behind her at the launch of Lynne Golding Australian Ballerina by Edith Pillsbury, Readings bookshop, Hawthorn in Melbourne, 2009

*Laurie Carew was the visual merchandiser responsible for the celebrated window display style of the exclusive department store Georges and although he was never a member of the Borovansky Ballet, he did appear with the company as an extra, so he was also included on the guest list of Borovansky Ballet reunions. According to Barry Kitcher, Carew, most notably, appeared as one of the two drummers flanking the puppet theatre stage in the Borovansky Ballet’s première season of Petrouchka (1951). This part involved marching forward to the edge of the stage and then retreating again. At the time, Carew was working at Myer and would take his lunch break to rush off to His Majesty’s Theatre for his appearance in the Wednesday matinees. Then he would rush back to the store, where his boss Fred Assmusen, who created Myer’s famous Christmas windows, would reprimand him with, ‘You’ve still got some make-up on!’

**John Cranko’s Gilbert and Sullivan inspired ballet Pineapple Poll was set to a score of Sullivan’s music arranged by Australian conductor Charles Mackerras, who like Stewart came from a Gilbert and Sullivan loving family and who, as a music student in the early 1940s, played oboe in a J.C. Williamson’s Gilbert and Sullivan season. He also worked as a rehearsal pianist for Kirsova. Although Pineapple Poll was made on the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (1951), the Borovansky Ballet was the second company on which Cranko mounted the work (1954) and Barry Kitcher danced in the première cast. It proved extremely popular, so much so that when Borovansky’s last ballerina Marilyn Jones was artistic director of The Australian Ballet, she included it in the triple-bill programme A Tribute to Edouard Borovansky of the 1980 season.

Biographical information about and direct quotes from Jean Stewart taken from author interviews with subject.

Thank you to Valda Jack (Lang), Barry Kitcher, Judy Leech, Dawn Kelly and Frank Van Straten for their extensive help with photographs and information in the preparation of this story.

[…] of the life and work of Jean Stewart than I was able to give see Blazenka Brysha’s story at this link, as well as an interesting comment from her about one of Stewart’s photos of Martin […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Michelle. The more I consider the achievements of our ballet (and dance!) pioneers, the more astounded I am by what they did and how they managed to do it.

LikeLike

Jean was a much loved member of our dog park community for many years. She was a force and a friend to all of us and our dogs .We miss her greatly

LikeLike

Jean was a regular at The National Theatre Ballet School performances while I was GM – we used to put her favourite seats to one side when setting up shows for sale. She was a regular donor in her life time & remembered the School in her will with unexpected generosity. R.I.P

LikeLike

Thank you, Robert, for yet another Jean Stewart story. Her contribution to the development of Australian ballet in the 20thC was multifaceted: her photography is a brilliant and invaluable visual record and her unfailing generosity was a most welcome moral and practical support.

LikeLike