While Noel Tovey’s whole dance CV is impressive enough for him to have been honoured by a prestigious peer industry Ausdance Lifetime Achievement Award (2017), his early years in dance have been overshadowed by both his later success on the international stage and all the other achievements of his remarkable life. However, Noel Tovey AM, Australia’s first ballet dancer of Aboriginal heritage, also has a presence in the context of mid-century Australian dance history that is in itself remarkable and deserves more attention than it has received to date.

While Noel Tovey’s whole dance CV is impressive enough for him to have been honoured by a prestigious peer industry Ausdance Lifetime Achievement Award (2017), his early years in dance have been overshadowed by both his later success on the international stage and all the other achievements of his remarkable life. However, Noel Tovey AM, Australia’s first ballet dancer of Aboriginal heritage, also has a presence in the context of mid-century Australian dance history that is in itself remarkable and deserves more attention than it has received to date.

Among other connections with this pivotal era of Australian dance history, Noel Tovey has an important link to the Borovansky Ballet although he only appeared with it as an extra, and to Laurel Martyn’s Ballet Guild with which he danced, most notably in Martyn’s seminal Australian ballet The Sentimental Bloke. Significantly, the interview for this story lead to the discovery of material showing his connection with both companies.

Among other connections with this pivotal era of Australian dance history, Noel Tovey has an important link to the Borovansky Ballet although he only appeared with it as an extra, and to Laurel Martyn’s Ballet Guild with which he danced, most notably in Martyn’s seminal Australian ballet The Sentimental Bloke. Significantly, the interview for this story lead to the discovery of material showing his connection with both companies.

Although Noel was then just an aspiring young dancer, he seems to have had the knack of being in the right place at the right time. Noel tends to regard the events of his life as stepping-stones on his way to other things but when it came to dance, he was actually hopscotching through history.

Noel Tovey AM is lauded as Australia’s first ballet dancer of Aboriginal heritage and has received multiple awards for his work in the performing arts, and as a community activist for, among other things, Indigenous and LGBTIQ rights, which is another important part of his history. Late last year he received notification that Flinders University was to award him an honorary Doctor of Letters.

Part of the citation stated:

Mr Tovey is openly gay and has spoken out for the rights of LGBT elders. In June 2010, Mr Tovey was recognised for his contribution to the LGBT community by becoming the 2010 recipient of the Foundation For All of Us Lifetime Achievement Award. In January 2015, he was made a member of the Order of Australia for significant service to the performing arts, to Indigenous performers and as an advocate for the LGBTI community and in the same year was inducted to the Victorian Aboriginal Honour Roll.

Just to emphasise the broad nature of Noel’s achievements it should be added that he is also an authority on aspects of 20th C ceramics design.

So, Noel’s life contains many stories and fortunately he is a great storyteller. As an artist working in performance, he expressed the story at hand as a dancer, singer, actor, choreographer, director and writer. As an author he has published two volumes of autobiography: Little Black Bastard (Hodder Headline, 2004) and its sequel And Then I Found Me (Magabala Books, 2017). A third volume Not So Little Anymore (working title) is written but still being refined.

Among his stories are a few that he made up to compensate for, and even hide, the ghastly realities of the life into which he was born. The suave, entitled Rohan Scott-Rohan fantasy-self of Noel’s young imagination was light years away from the little black bastard of his actual birth.

But while Noel was busy chalking up one achievement after another, he kept that early biographical past well hidden, even from himself at times, lest his life unravel under the burden of unendurable memories.

Born in Melbourne in the depths of the Great Depression into a life of poverty and abuse, Noel always thought himself black because his father was black. He only learned his family history bit by bit. He was the grandson of James Bohee, an African Canadian musician and singer who performed with his brother George as the Royal Bohee Brothers. The internationally successful duo was able to add the word ‘Royal’ to the name of their act because they not only entertained the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, but also because James gave him banjo lessons. Noel’s father Frederick Morton, a musician, singer and dancer, was the illegitimate son of James and a white English woman. His mother was the granddaughter of an Aboriginal woman as well as having a Maori bloodline.

Noel’s first book Little Black Bastard records the harrowing details of his childhood, including years of sexual abuse, especially following his removal by the state from the alcohol fueled dire neglect by his parents.

One of Noel’s very early memories is of his sister and him dressed in clown suits, collecting pennies from the ground while their father busked in the street. Frederick Morton was known to the police as a ‘dope peddler.’ Noel only remembers that he was a dapper dresser and had a beautiful singing voice. Not surprisingly then, Noel’s own first performance was as a singer, entertaining his school class with Old MacDonald. The rendition, which included ‘animal noises and impersonations’ (LBB p 47), was a big success and is a happier memory from the time after the state placed him and his sister in the care of a man who sexually abused them for five years before being jailed for just a small part of his pedophilia.

One of Noel’s very early memories is of his sister and him dressed in clown suits, collecting pennies from the ground while their father busked in the street. Frederick Morton was known to the police as a ‘dope peddler.’ Noel only remembers that he was a dapper dresser and had a beautiful singing voice. Not surprisingly then, Noel’s own first performance was as a singer, entertaining his school class with Old MacDonald. The rendition, which included ‘animal noises and impersonations’ (LBB p 47), was a big success and is a happier memory from the time after the state placed him and his sister in the care of a man who sexually abused them for five years before being jailed for just a small part of his pedophilia.

Although Noel did eventually perform professionally as a singer on occasion in the future, the road that took him from the horror of his beginnings was the one on which he made his dance journey, which opened up the roads that took him to success as a multi-talented theatre professional, as a political and social justice activist, and finally to himself. Whether this was fate at work, or just co-incidence is anyone’s guess but Noel’s life in its various guises seems to have been totally shaped by inexplicable twists and turns.

It is because Noel’s life has been such an exceptional one on the personal, professional and public levels that his dance background and career have tended to be obscured by all the other fascinating and impressive things about him. In fact, Noel’s life story is composed of so many different threads that the only way he could tell it was by devising a unique narrative style, which draws on both the oral traditions of his ancient Australian Indigenous forebears and the dramatic monologues and soliloquies of the much more recently evolved English drama. The result is not linear and sequential but rather free-rangingly contextual, with aspects of his life coming into focus and receding as the narrative unfolds.

While dance features only marginally in Noel’s widely read Little Black Bastard, the work reveals the heart of a dancer:

I loved ballet lessons. The music and movement released something in me that was akin to what I felt when I skated, only more so. When I danced it was in my world and nobody else was there. It was as though I had been dancing for a thousand years or more. I could feel it in my bones. Without knowing it, I was connecting with my culture through dance—not that I was aware of it at the time. (p111)

In the unpublished third volume of his autobiography (Not So Little Anymore pdf), Noel encapsulates the transformative powers of dance for release and catharsis:

In my world of dance there were no drunks, no drugs, no abuse and no racism, it was just me and the music. Sometimes now, I sit in my wheel chair put my favourite record on the turntable close my eyes and I’m dancing again. (p 212)

So, when did Noel’s dance story begin? Without hesitation, he says, ‘My dance journey began when the police told me I had to get a job and I got a job at Collins Book Depot and a girl—Chesca—took me to a student performance of Les Sylphides and at the end of the male solo she dug me in the ribs and said, “You could do this.” It was like a light going on. I knew I could.’

‘Chesca,’ as Miss Frances Curtis liked to be known among the Melbourne’s artistic and intellectual bohemians of the late 1940s and early ‘50s, was only a few years older than Noel but she provided the inspiration and fuel for his ambitious autodidactism, which was comprehensive by any standards and awe-inspiring in a teenage street kid who had barely set foot in school. Having relied on newspapers and a dictionary for his education to that point, the 14 year-old Noel immersed himself in literature, philosophy and the arts. The dictionary became his constant companion.

Chesca not only took Noel to the Les Sylphides performance but also furnished him with the name and address of the National Theatre Ballet School whose students had danced it. Although Noel was by then an accomplished ice-skater, which was helpful for learning ballet moves like turns and jumps, his subsequent experience as a beginner at that school was a mixed one largely due to friction with other male students and the teacher Miss Jean Alexander. Writing about this in Little Black Bastard Noel concluded, ‘I didn’t last too long at the National School.’ (p 112)

Looking back now, Noel says, ‘I didn’t think the teacher was very good.’ He doesn’t name Jean Alexander in our discussion but readily admits he means her. He did also name her in Little Black Bastard as his first teacher but made no comment about the quality of her teaching, which was doubtful at best and mostly overlooked as an embarrassment by the ballet community because of her more successful role of over forty years at the National as a facilitator.

The National Theatre Ballet School was part of the National Theatre Movement started in the mid-1930s by soprano turned creative director and administrator Gertrude Johnson. Her mission was to establish a strong foundation for Australian performing arts by training practitioners and mounting performances. To that end, drama and opera schools were established and Miss Jean Alexander, a teacher of musical interpretation, was hired (1939) to run a ballet school supplying dancers and choreography for the various productions.1

Alexander designated herself a choreographer while mainly hiring others to teach dance classes. Noel may not have made his retreat had he still been at the school in 1949 when Alexander recruited Madam Lucie Saronova , a student of Cecchetti and founder of the Cecchetti movement in Australia, to head the teaching for her. It was through Saronova’s work that the school became a leading ballet training institution.2

Nevertheless, Noel did join the National Theatre Movement later, which not only gave him opportunities to appear on stage as an extra in dramas and even operas but allowed him to see for free the many productions staged by the National, which in itself provided a valuable education.

In the emotional moment of his acceptance speech for his Ausdance Lifetime Achievement Award, Noel mistakenly credited Jean Alexander with giving him free lessons. That distinction belonged only to Madam Borovansky and is on record in Little Black Bastard. While Alexander didn’t give Noel free lessons, she still had a positive influence because although he left the National Theatre Ballet School, he subsequently devoted himself to learning the art more seriously.

Looking back on his days at the National school, he now says, ‘I left there and went to Madam Borovansky and that was the real beginning of my career.’

By all accounts, Madam Xenia Borovansky was quite fond of Noel. ‘She was and she said to me, “You’re too tall, darling, but you’re quite talented.” So in a way she was responsible for me being a dancer. She said to me, “You have to do four classes a week,” and I said I can only afford one. She said, “I’ll give you the other three, if you clean the studio for me.” So I did. I started cleaning the studio and I really liked her.’

In Little Black Bastard Noel wrote, ‘When I look back at all the teachers I had in my long career, I would have to say that when it came to teaching style there was no one better than Madam Boro.’ (p114)

As luck would have it, Noel was at the Borovansky academy when Edouard Borovansky assembled his company for the 1951/52 Jubilee season celebrating the first 50 years of Australian federation. With the privations of the World War II in the past by then and the promise of a prosperous and exciting future ahead, the general mood was one of positive outlook and belief in advancement. Ballet was not to be left behind.

For Edouard Borovansky there was even more at stake to prompt the Jubilee season. Having worked very hard for over a decade to build Australia’s first successful professional ballet company, Borovansky suddenly faced some formidable competition from the National Theatre Ballet Company, another Gertrude Johnson initiative. It was formed in 1949 under the direction of Joyce Graeme, a leading principal of Ballet Rambert during its Australian tour (1947–49), who recruited some other ex-Rambert talent, including Margaret Scott, and a line-up of impressive young local talent sourced via national auditions. The company set the highest standards on all counts and made history early in 1951 when it staged a magnificent production of Australia’s first full (four act) version of Swan Lake. No-one who saw it, including Noel Tovey, was able to forget it or the stunning performance by Lynne Golding in the dual role of Odette/Odile. In fact, Noel brings it up when I asked him about seeing other companies including Ballet Rambert, whose lengthy tour overlapped with his ballet beginnings.

While Noel had seen Rambert and even queued for leading ballerina Sally Gilmour’s autograph, in our interview he was keen to talk about something he has not mentioned in his writings: Lynne Golding’s debut in that Swan Lake because by 1951 he was already a fan of her work, having been memorably dazzled by her as the Tivoli’s resident ballerina.

The ever-popular Swan Lake Act 2, a staple of early to mid-20th C repertoire was well known to Australian audiences. There is even existing footage of the Borovansky Ballet performing it in the 1940s. It is not surprising then that Borovansky was among the first to understand the major significance of The National Theatre Ballet’s achievement with its full Swan Lake. In fact, he made his entire company go to see it and at the end they stood up and cheered.3

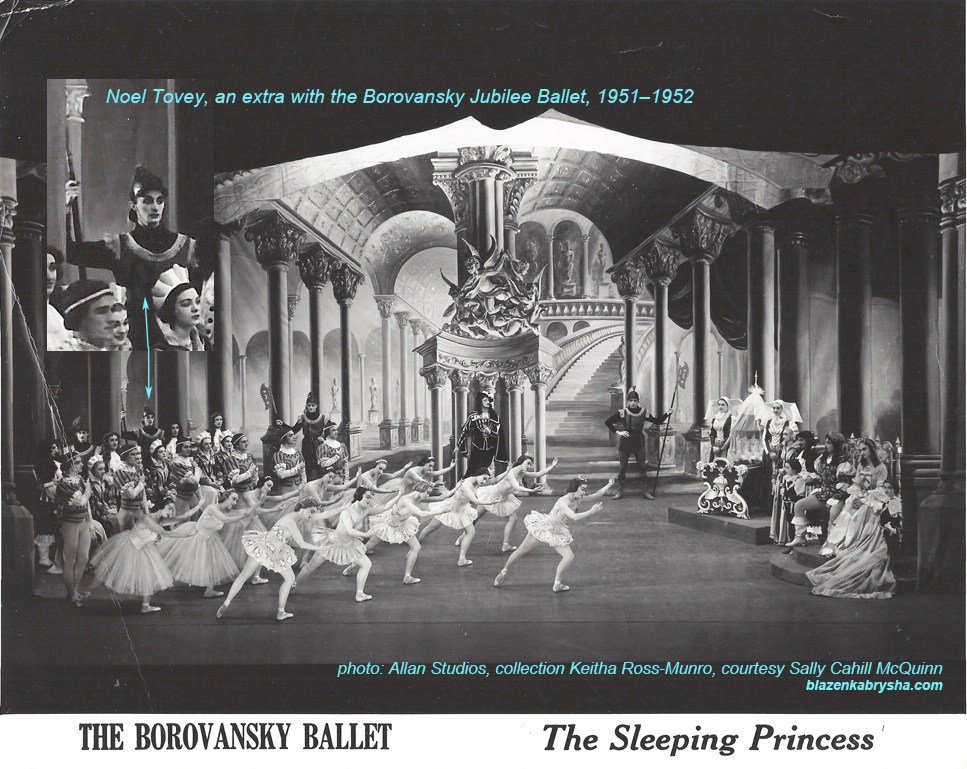

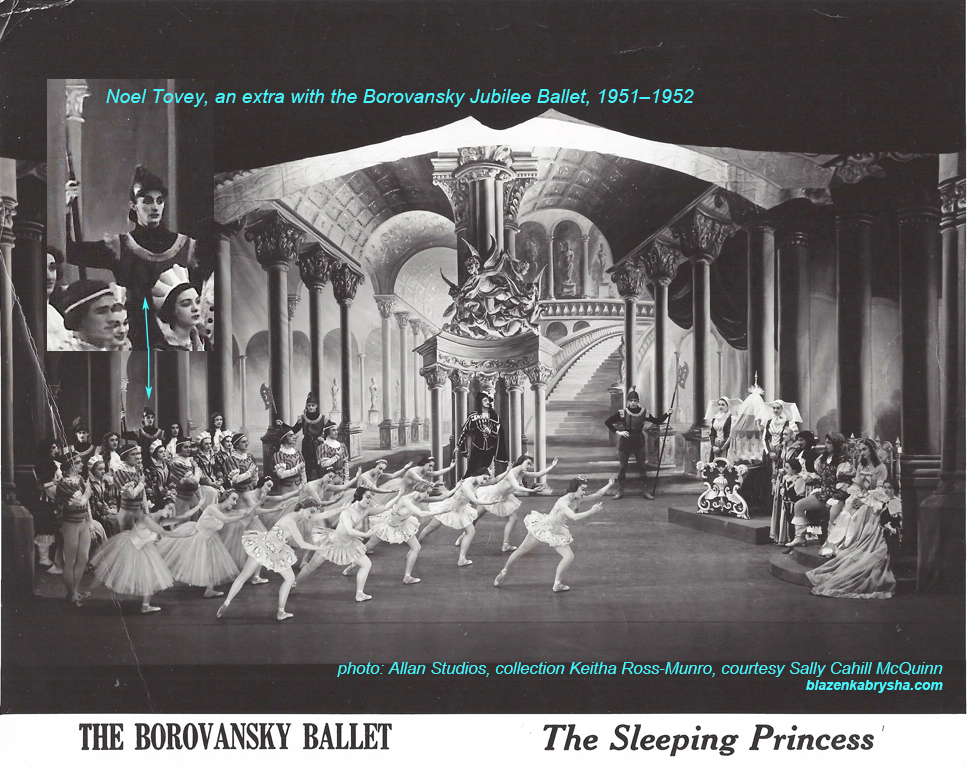

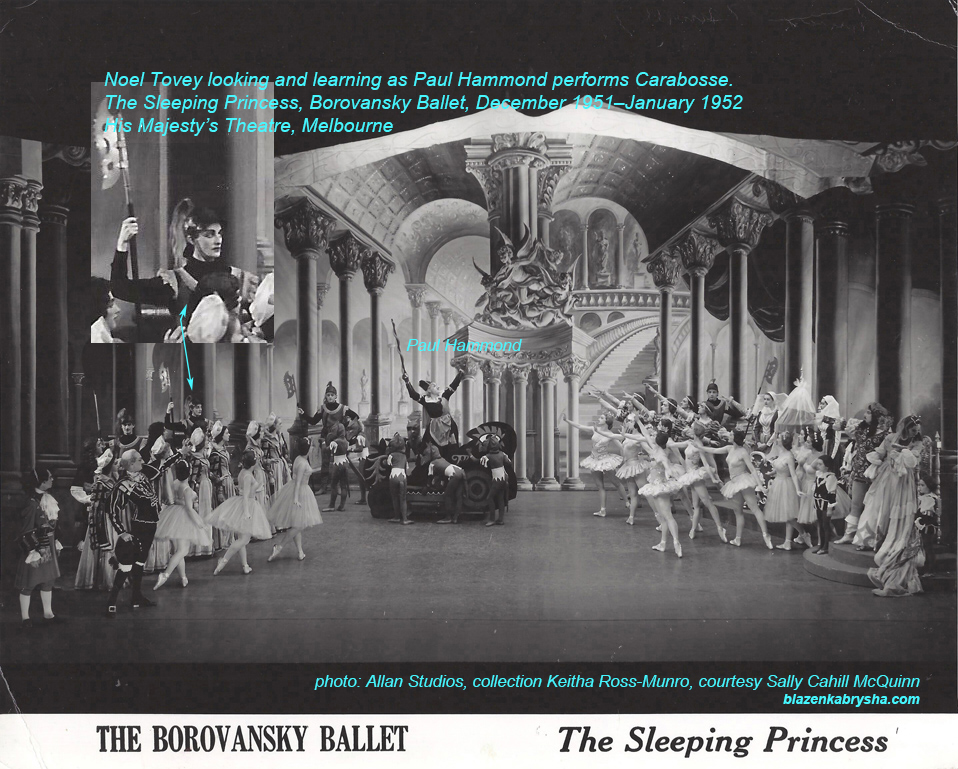

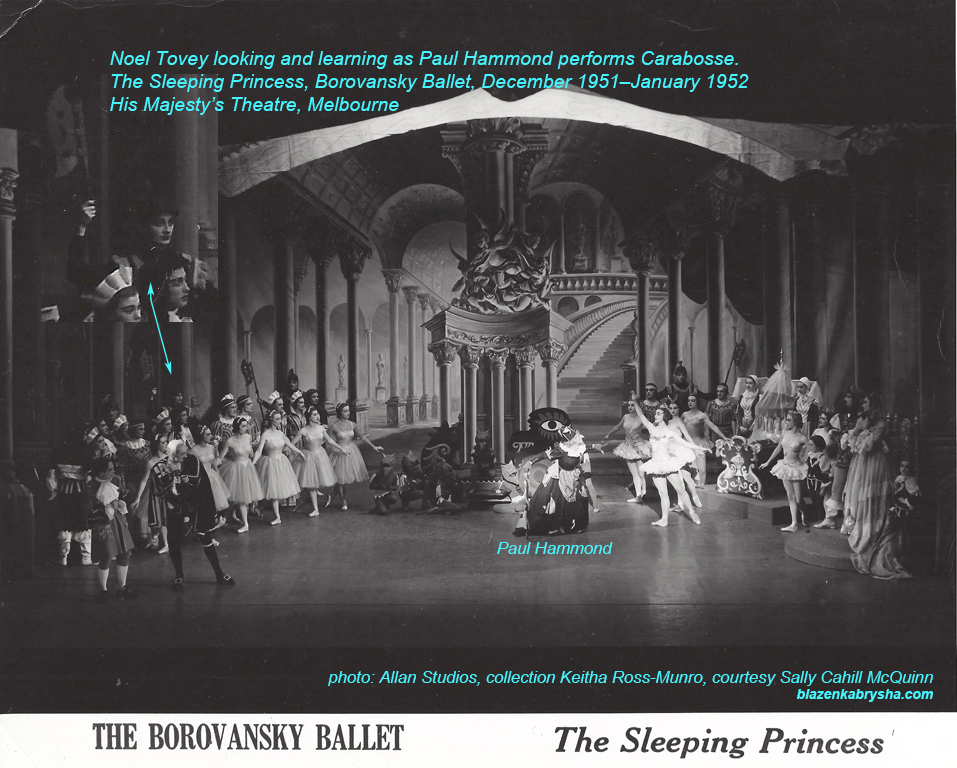

Borovansky responded with a daunting reply in the Jubilee season which featured a number of programmes and various premieres, most notably The Sleeping Princess, which became a ballet box-office record breaker. Altogether, this was the most spectacular single season ever mounted by Borovansky and Noel was in three ballets over three programmes during the company’s Melbourne appearance.

Although by this stage of his training Noel was far from ready to be taken into the Borovansky Ballet as a member, Borovansky did select him as an extra. Lest there be any confusion about his exact status, Noel is the first to point out that he was never in the Borovansky company but only an extra. By this understanding of hierarchies he actually reveals his Borovansky Ballet credentials because while the company used many additional performers, mostly senior ballet students, its membership was carefully limited given the severe financial constraints under which the company was able to maintain professional status. From the outset, Borovansky alumni have been very protective of their status. Noel’s implicit acceptance of this reveals him as a true insider.

In writing about his stint as an extra selected by Borovansky, Noel only mentioned Scheherazade and Petrouchka. In our interview he reveals that he was also in The Sleeping Princess. Pressed about his part he says, ‘I was a spear carrier.’

The Sleeping Princess, which premiered on 22.12.1952 at His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, was a direct response to the National Theatre Ballet’s Swan Lake and like it remains a major milestone in Australian ballet history as a first full staging of a major classic magnificently presented. Produced and directed by Borovansky, it featured choreography by Miro Zloch after Petipa and glorious design by William Constable. The company was blessed with three very popular and highly accomplished ballerinas to fill the bravura princess role: Edna Busse, Kathleen Gorham and Peggy Sager. Noel still lights up when he says, ‘I saw the wonderful Edna Busse dance the Princess!’

The Sleeping Princess, which premiered on 22.12.1952 at His Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, was a direct response to the National Theatre Ballet’s Swan Lake and like it remains a major milestone in Australian ballet history as a first full staging of a major classic magnificently presented. Produced and directed by Borovansky, it featured choreography by Miro Zloch after Petipa and glorious design by William Constable. The company was blessed with three very popular and highly accomplished ballerinas to fill the bravura princess role: Edna Busse, Kathleen Gorham and Peggy Sager. Noel still lights up when he says, ‘I saw the wonderful Edna Busse dance the Princess!’

While Noel did not have much to do with Borovansky, he considers him as ‘a forerunner. He formed a company and he put it into His Majesty’s when I was there. He was wonderful as a dancer, especially as the Strongman in Le Beau Danube.’

Noel was able to see Borovansky in this signature role because Le Beau Danube was on the same Jubilee programme as Petrouchka.

When Noel wrote about the Jubilee season in Little Black Bastard his only elaboration on appearing in Scheherazade and Petrouchka was about getting told off by assistant stage manager Colleen Gough for wearing too much make-up. Looking back now in the context of our intensive dance discussion he is ready to add a revelation that places his younger self in a much more serious light. He says:

Colleen Gough told me off because I had too much makeup on and all of that but, you know, we drew straws amongst the extras in The Sleeping Princess to see who was to faint on stage because standing in this ridiculous costume holding a spear up was too much, and it was me. In fact we did that ballet in the summer and I threw a faint on stage. Then Boro had a meeting with us and he changed the costume.

So, by chance and through no choice on his part, Noel was cast as an activist, a role he assumed more and more on much more serious matters as the years passed. By another twist of fate and in dealing with another matter, it is through the ballet collection of Colleen Gough’s boss Borovansky Ballet stage manager Keitha Ross Munro that I was able to source multiple hard copy original photos of The Sleeping Princess in which Noel can easily identify himself as one of the Palace Guards, the official name for the spear holder role.

Noel has very fond memories of his days with Madam Borovansky and smiles when he says, ‘All the little girls used to wear white tutus and I remember one, Alida Glasbeek, I don’t know what happened to her but she was quite talented as a child.’4

Noel has expressed regret in the past that he didn’t work harder when he was with Madam Borovansky. He also didn’t stay as long with her as did others who went on to professional dance careers. Referring to that time he says, ‘But I also went to the Ballet Guild, where Laurel gave me the opportunity to dance. I was in The Sentimental Bloke, I was in all sorts of things like En Cirque, for instance. We did En Cirque in the gardens.’

As director of Ballet Guild, Laurel Martyn was dedicated to creating Australian dance by fostering original local choreography, music and design, and training Australian dancers for performing it. While she had been Borovansky’s first ballerina and was instrumental in the formation and early running of his company, her vision for Australian dance and her core interest in creativity took her in a new direction.

Although The Sentimental Bloke ballet was based on the eponymous suite of poems by C J Dennis, a much loved classic of the Australiana genre, what made it fit Martyn’s principles for ‘Australian dance’ was her original choreography, its performance by Australian trained dancers, John Tallis’ commissioned score, and Charles Bush’s sets, and his costumes based on the Hal Gye illustrations in the first print edition of the poems. Noel was cast as one of the Blokes, not in the premiere performance in March, 1952 but later that year. In the programme he is billed as Noel Mortan, a misspelling of Morton, which was his father’s surname.

Throughout her work with Ballet Guild (later Victorian Ballet Guild and then Ballet Victoria) Laurel Martyn enabled many dance careers to begin and/or to be sustained. She went to great efforts to pay her dancers. While Noel was paid approximately the same for both his appearance with the Borovansky Ballet and with Ballet Guild—he says, ‘I think I got 12/- a week each for both but I can’t remember,’—considering that Martyn gave him the opportunity to dance and billed him as a Ballet Guild dancer, Noel’s first professional engagement as a dancer was with Ballet Guild.

The Ballet Guild programme from 1952 naming ‘Noel Mortan’—a misspelling of Morton, the surname by which he was known at that time. Jane Andrewartha, Executive Director of the Laurel Martyn Foundation kindly supplied this copy. At the time of the above performance ballet photographer Jean Stewart was stage manager and it is very likely that photos of Noel in this ballet also exist in the State Library of Victoria to which Stewart gave much of her photographic work. So far no such photos have been discovered in the Laurel Martyn Foundation archives.

Enlargement of details from the programme listing Noel Tovey as one of the Blokes.

It was soon after this that Noel Morton started using the surname Tovey, which had belonged to his mother and was on his birth certificate because he was illegitimate. Having been caught up in a police set-up and as a result tricked into being convicted of ‘the abominable act of buggery’, Noel needed every resource at his disposal to disassociate himself from his criminal record and get his life back on track. It needs to be mentioned that homosexuality was decriminalised in Victoria in1981 and in 2015 those convicted of the former crime could have their records expunged. Noel was among the first to apply. Eventually those convicted of the former crime received an official apology.

Speaking of his days as a ballet student, Noel says, ‘Laurel as a teacher was very strict but I can’t remember much about her to be honest. She choreographed the ballets and the boys were second to the girls in those days. But Madam Boro was really responsible for me as a dancer. She would come around with a stick and point at my feet with the stick on the instep, saying, “Point it.”’

So, while Laurel Martyn was the first to engage Noel as a professional dancer, he regards his professional dance career as formally beginning in 1954 with Paint Your Wagon and a pay of £13 a week. Getting that job is another example of Noel’s uncanny ability to be in the right place at the right time. He was walking past Her Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne, and ran into fellow dancer Janette Liddell who had been inside rehearsing for the musical. She mentioned that due to injury they were short of a male dancer and took Noel in to audition for the English choreographer Maggie Maxwell. That Noel should have known Liddell is not surprising considering how small and interconnected the Melbourne dance community was even into the late 20thC, let alone 65 years ago. What surprises is that Noel first knew her because she was Cheska’s cousin.

Young Noel. A photo from his days in Paint Your Wagon.

Adding another uncanny twist to Noel’s first dance job story is the fact that another woman he also knew from his Collins Book Depot job, Betty Pounder, was ballet mistress for Paint Your Wagon. Unfortunately she had wanted another dancer to have the job that Noel got, which resulted in a permanent animosity and no work for Noel where Betty Pounder had a say. Given that she rose to a very powerful position as a highly regarded dance director and much admired choreographer in the JC Williamson Theatres empire, this was very bad luck for Noel. By the same token, Noel is quick to give credit where he feels it is due and points out that he was able to ‘repay Maggie’ Maxwell, for whom he also later worked in England, ‘by hiring her as ballet mistress for restaging O! Calcutta,’ in London’s West End in the 1970s.

But just as Noel found himself unwelcome at JCW’s he found an ally at the Princess Theatre in Kitty Carroll. He says,

Going to the Princess was the making of me. My father had worked with Kitty Carroll, who was Mrs Carroll (wife of theatrical entrepreneur Garnet Carroll, owner of the Princess Theatre) when she was an obscure soubrette. She always sat in the box and I remember her calling out across to the English director Stanley Willis-Croft ‘Take the tall dark boy on the end, we always use him.’

Noel, always welcome at the Princess Theatre, dancing in The Music Man, 1959.

Noel also found work as a dancer at the Tivoli Theatre with its continuing inclusion of dance in its regular programmes. As mentioned, Noel’s first introduction to ballerina Lynne Golding’s work was at the Tivoli. It was also at the Tivoli that Noel saw mid-century Borovansky Ballet legend Martin Rubinstein who danced there in the later 1940s both under his own auspices as well as with Ballet Guild during the Borovansky company’s recess periods. The Tivoli’s variety bills provided high quality popular theatrical entertainment to the masses at affordable prices. Noel clearly enjoyed the mixed fare on offer, indicating that dance alone was not the be all and end all for him, as it was to those who made their careers exclusively in dance, even if they never rose to the stardom of a Golding or Rubinstein.

Dancing at the Tivoli: Showboat, 1963

So, while Noel was progressing as a dancer, he had also seriously branched out into drama via his association with the National Theatre and thereby started another important aspect of his career. Through dancing in musicals he forged a life long friendship with Robina Beard OAM, who also had a distinguished career in various facets of theatre as well as dance. Thanks to their parallel theatrical talents they would also go on to work together very successfully as seasoned professionals, most notably on Noel’s acclaimed stage version of his Little Black Bastard, which Beard directed.

In My Life: your’re soaking in it the autobiography of her eventful and successful life, Noel Tovey’s close friend and colleague Robina Beard also writes about her association with Noel, including directing him in the stage version of his book Little Black Bastard.

Meanwhile, the young Noel continued to train in dance with some major teachers both in Australia and then, from the early 1960s onwards, abroad. Although it is on record that Noel studied modern European dance and improvisation with Hanny Exiner, it’s a revelation to hear him say, ‘I had private lessons from Paul Hammond and Maggie Scott. She introduced me to Audrey de Vos’s work. Audrey de Vos taught ballet in a circle, everything was balanced. You imagine a circle and you work in that space.’

Noel knew Paul Hammond from the Borovansky Ballet with which he was a leading soloist and ballet master. It was while Noel was an extra during the Jubilee season that Hammond performed his two most acclaimed roles: the Charlatan in Petrouchka and Carabosse in The Sleeping Princess. It gave Noel a privileged opportunity to look and learn and he certainly took it as shown in the Borovansky Ballet Sleeping Princess photographs from the Keitha Ross-Monro Collection.

Noel knew Paul Hammond from the Borovansky Ballet with which he was a leading soloist and ballet master. It was while Noel was an extra during the Jubilee season that Hammond performed his two most acclaimed roles: the Charlatan in Petrouchka and Carabosse in The Sleeping Princess. It gave Noel a privileged opportunity to look and learn and he certainly took it as shown in the Borovansky Ballet Sleeping Princess photographs from the Keitha Ross-Monro Collection.

During the Borovansky Ballet’s recess periods dancers needed to find alternative employment and like many of his contemporaries, Hammond taught ballet, having opened a school with his then wife, Borovansky Ballet ballerina Peggy Sager. When they went on tour with the company they asked Margaret Scott to take over for them. Subsequently she started her own school, specialising in keeping professional dancers fully trained between performance jobs because in Australia of that era there was no such thing as continuous professional employment for dancers.

Scott became the founding director of The Australian Ballet School, a post she held until 1990, during which time she had a pervasive impact on the development of Australian dance artists in ballet and beyond. In quest of best outcomes, over the years she hired a wide range of specialist teachers including Paul Hammond who among other things taught ballet history at the school and also filled the role of Archivist. In recognition of her work she received many honours including being made a Dame Commander of the British Empire.

Paul Hammond received an OAM for his work, which also included producing a number of ballet dancers who attained prominent careers, among them Gailene Stock, who not only took over from Dame Margaret as director of the ABS, but went on to head the Royal Ballet School.

While Noel created his own chapters of Australian ballet history, his direct connection with major figures like Dame Margaret Scott and Paul Hammond are noteworthy details in that context.

There is a saying that ‘when the student is ready, the teacher will appear.’ It could have been coined with Noel in mind. When Dame Margaret taught Noel she must have recognised, like Madam Borovansky, that he was not your usual ballet hopeful and tailored her teaching to be of value to him. It is noteworthy that Dame Margaret not only chose to reference de Vos’s approach in teaching Noel but that she also acknowledged this in sharing her understanding of it with him. Audrey de Vos (1900–1983), a student of Astafieva and Novikoff, tailored her teaching to suit the individual needs of dancers, cultivating an understanding of anatomy to allow ease of movement while engaging body and mind in facilitating the expressiveness that could be accessed through this approach.5

Dame Margaret, as a professional dancer of the 1940s in London, would have been familiar with the work of de Vos, which was popular among professional dancers because of her strategies for overcoming each dancer’s individual movement problems but also for enhancing strengths. From Noel’s description of Dame Margaret’s work with him, it seems that she was working on developing his placement and line as a dancer. Judging by photos of Noel performing, he has beautiful line so we can extrapolate that in his case Dame Margaret was working on his strengths rather than weaknesses. Among all the attributes Dame Margaret brought to any of her work, effectiveness and economy would always rank highly.6 A driven personality like Noel’s would have been ideally suited to a results targeted approach.

Beautiful line, one of Noel’s finest qualities as a dancer, displayed here to perfection as he partners Suzanne Kerchiss in the 1967 revival of Sandy Wilson’s The Boy Friend, Comedy Theatre, London. Wilson asked Noel to choreograph the production and suggested he dance the Tango sequence. It turned out to be a highlight of Noel’s dance career. In Little Black Bastard Noel mentions that among the fragments of information his mother told him about his father was the claim that he was ‘one of the first people to demonstrate the tango in Australia in the mid twenties.’

While Noel’s interest in theatre went beyond just dance, so his interest in dance went beyond just ballet. He says, ‘I went to Hanny Exiner for modern European improvisation, which I found wonderful. Strangely enough it was at that point that a psychiatrist said to me, “Oh, it would be alright if you just went out into the jungle and danced to the drum beats.”’

As luck would have it, Katherine Dunham, African American dance pioneer, brought her internationally acclaimed company to Melbourne in May–August 1956. Noel introduced himself and Dunham took him on as an apprentice. Speaking of her, Noel says, ‘Miss Dunham called me ‘high yaller’ because I was a mixture of white and black. Every morning Miss Dunham would take a ballet class, which we would all applaud her for. Then Lenwood Morris would take over, the drummers would appear and he taught us Dunham technique.’

It was the latter classes that excited Noel. While Noel describes Dunham technique as being essentially ‘all about walking and hips and contractions,’ its combination of ballet and Afro Carribean dance would have been tailor made for him at this stage of his development as a dancer. Dunham’s visit also had a profound effect on Noel’s colleague Janette Liddell, who became one of the few white people ever to be taken into the Dunham company, in which Noel describes her as having been fantastic. Liddell went on to become a noted teacher of jazz ballet and also gave Afro Dance classes.

It was ten years later in Italy that Noel got to work with Dunham, when she was choreographer on John Houston’s movie The Bible, In the Beginning, and cast him in the Sodom and Gomorrah orgy scene. By that stage Noel’s dance journey had been intensive and multi faceted. He says:

I had felt that ballet was too restricting. So, I went to Hanny Exiner, and I went to Dunham technique; that loosened me, it freed me. I think ballet is very limiting. I did flamenco with Luisillo, when his company Spanish Dance Theatre came to Melbourne (1958), which was amazing. I also learned flamenco from Teresa Amaya, who was a principal dancer with the company. She was the only one allowed to wear the long dress because only Gypsies can wear the long dress; the others wore the short dress. There was no company (here) like that, it was all new.’

Noel was acquainted with tap dancing from early on.

A girl taught me to tap in North Melbourne. Miss Hazel Moore taught Kathy in her house and this girl, whom I met many years later at a reunion, taught me to tap in the street. She would pass on to me everything she had learned at Miss Moore’s.

His formal tap lessons were with Betty Meddings, ballet mistress/choreographer who worked on stage shows for major theatres and on TV. He ended up working for her doing various types of dancing on the TV show Sunnyside Up! in the early 1960s. That was during one of his brief visits to Australia, which he had left for England in 1960. With the exception of visits either for family reasons or work, Noel ended up living overseas, mainly in London, for more than 30 years.

Beyond Australian shores, Noel also studied different dance styles dance with notable authorities including Alvin Ailey, Matt Mattox and Martha Graham. He learned classical Indian dance from Ram Gopal and Jack Cole. While Jack Cole is principally known for his seminal work in theatrical jazz dance, which is a morphing of a range of styles, he was trained in Bharata Natyam and that’s what Noel learned from him. He says, ‘The philosophy behind Indian dance really appeals to me: where the heart goes, the hand goes, and the eyes follow. I was keen to learn everything because a choreographer has to learn everything.’

Beyond Australian shores, Noel also studied different dance styles dance with notable authorities including Alvin Ailey, Matt Mattox and Martha Graham. He learned classical Indian dance from Ram Gopal and Jack Cole. While Jack Cole is principally known for his seminal work in theatrical jazz dance, which is a morphing of a range of styles, he was trained in Bharata Natyam and that’s what Noel learned from him. He says, ‘The philosophy behind Indian dance really appeals to me: where the heart goes, the hand goes, and the eyes follow. I was keen to learn everything because a choreographer has to learn everything.’

This wholelistic approach served Noel well. By the time his career really took off in the 1960s in England, he was well versed in dance, drama and song. In Australia he had studied drama with Hayes Gordon, who encouraged him to study extensively in all the theatre arts. Noel learned singing from Joan Arnold at the Melbourne Conservatorium. Noel’s studies beyond dance also continued overseas. One of his first jobs in England was working with the legendary Stella Adler on the London premiere season of Arthur Kopit’s absurdist play Oh Dad, Poor Dad, and later he went on to study with Uta Hagen.

But theatre was always at the back of Noel’s mind. He had had elocution lessons as a child and from the age of 14 started joining amateur companies. He believes that he inherited his talents for performance and theatre, saying, ‘I inherited all of it. My father was addicted to cocaine but he was also a singer, and a dancer. My great grandfather was a slave in Africa and this whole natural thing was born in me.’

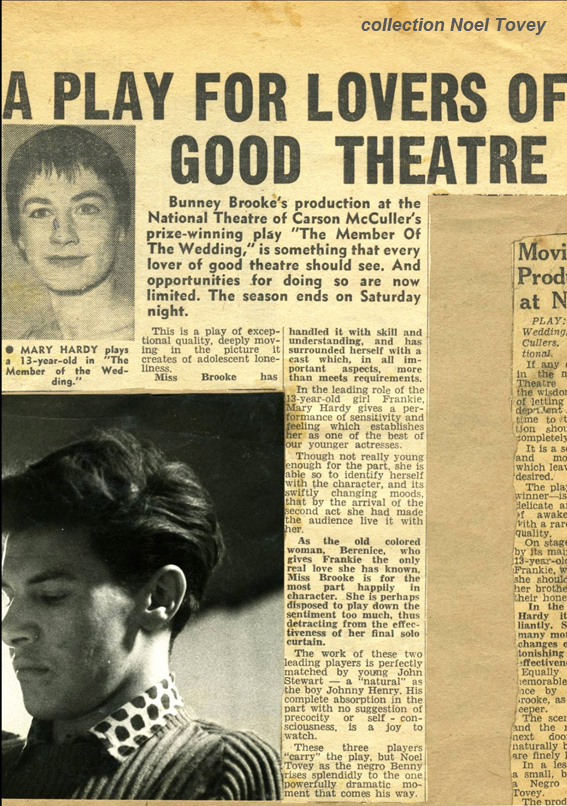

Noel Tovey’s first review as a professional actor.

Fast forward some ten years. While Noel had already danced as a principal with the Sadlers Wells Opera, the photograph above shows him in an acting role with the Covent Garden Opera Company in the London premiere of Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron at the Royal Opera House, 1965.

One way or another, he was always studying. In the case of his dance teachers, he not only learned during class but also he ‘would watch them after class, how they walked, how they moved. Dancing is a complete movement art.’

This approach added another skill set to Noel’s professional abilities:

I had a reputation for working with nondancers and it was built on the basis that I would watch them walk, how they moved and I would incorporate that. It’s ridiculous that you would think you can get a nondancer to dance a ballet when they haven’t spent years of training. It took me years of training. I remember I paid 12 and six for a quarter of an hour skating lessons (in early adolescence). I remember all my money went on lessons: singing lessons, dancing lessons, lessons, lessons!

In view of all that, what advice would Noel give young dancers?

I would say concentrate on the body, the expression of the body and listen to what your teachers are telling you. Not every teacher is a good teacher. Not every teacher is Madam Boro, for instance, who decided that she would be a teacher very young and she passed on (her knowledge). I see so many bad dancers today. For example, I see in a dance magazine a boy of 11 or 12 stretching his leg but it’s over(extended) and they’re losing the line. Line is about perfection and they’re losing the line for standing splits—which I hate.

They’re pushing it too far. I think that dance is about the music, expressing the music and expressing the thing (what) you are. Boys, and I’m speaking about boys now, have forgotten how to present themselves on stage. For instance, the one thing I had was presentation, I was a performer.

Noel with Jade, the daughter of close friends who are also theatre professionals. The photo was taken at the Lincoln Centre, New York, 2005. Noel doesn’t remember the details of the occasion but thinks Jade may have been auditioning for something like Nutcracker.

A highlight of Noel’s dance career was in 1967 when Sandy Wilson invited him to choreograph the London revival of his musical The Boy Friend. Wilson also suggested that Noel himself dance the Tango sequence. This resulted in a hit and one of Noel’s finest dance moments. It’s the first that springs to mind when I ask him about his best dance memory. He answers:

Hearing people cheer when I finished the Tango in The Boy Friend. I couldn’t believe they were cheering me. Suzanne Kerchiss who partnered me was wonderful. She said, think of it as somebody else’s choreography. I was so paralysed with nerves but then when the audience started cheering, I couldn’t believe I actually choreographed it.

Although Noel’s many triumphs in the theatre and beyond it are the product of his own relentless work, others’ recognition of his efforts always seems to surprise him. He could never be considered a tall poppy.

Noel Tovey’s inimitable sense of style shows in this photo of Anything Goes, which he directed and choreographed, Richbrooke Theatre, Sydney, 1971

On the other hand, it’s not stoicism that enables him to deal with all the hardships he has endured over his life time but rather an acceptance that springs from something in him akin to mysticism. Noel’s attraction to classical Indian dance is not the only affinity he has with Eastern philosophy. His sister, who sometimes helped with police investigations as a forensic psychic, once told him, ‘You won’t ever be a medium like me, you’ll be a mystic.’

Noel’s greatest ordeal in recent years has been the loss of a leg. He speaks of it with great calmness, ‘I lost this leg because I was raped when I was 4 years old by a drunken uncle and in the dislocation cancer grew, it took 75 year to grow. Then I lost the leg because the surgeon made a mistake.’

While he agrees that it is all very bad luck, he points out, ‘But I’ve had to accept it.’

In fact, asked whether he would have swapped his life with all its ups and downs for one on an even keel, he says, most positively, ‘No, not at all! I mean, I am what I am and I’ve always been what I am from way back…’

Noel at home surrounded by some of his art collection, 2019.

As our interview winds down and Noel becomes quietly reflective, I say, ‘You must have a lot of memories.’

Yeah,’ he replies wistfully, ‘I was thinking about Madam Borovansky, I think a lot about her these days, in as much as she really was responsible for me being a dancer.’

He agrees that she was kind, a quality that endeared her to so many of her students, but he qualifies this, saying,

She was kind but not in class; she was very much a teacher in class. We always had a pianist and when Madam Borovansky took the boys separately form the girls, it was an amazing experience because she would say to the girls, ‘dance,’ and she would say to the boys, ‘Noel, not you’ and she would say, ‘darling you’re too tall to be a dancer, think of you carrying a cloud.

She, of course, was tall, I point out.

‘She was very tall…’ he concludes emphatically.

Though now in his 80s and wheelchair bound, he remains a dancer. Elegantly pulling up from his sedentary position to demonstrate a de Vos concept that Dame Margaret Scott taught him, he stretches out his right arm, fingers pointing to infinity, while he uses words to indicate where the foot and the leg would go. It is a moment of dance magic.

Blazenka Brysha

Thanks to Noel Tovey for his patience and grace in answering endless questions; to Jane Andrewartha for sifting through Laurel Martyn Foundation archives in quest of information about Noel’s time with Ballet Guild; and to Sally Cahill McQuinn for permission to use the photographs from the collection of her mother Keitha Ross Munro.

Footnotes

1 Brissenden, Alan, and Glennon, Keith, Australia dances: creating Australian dance 1945–1965 (Wakefield Press, 2010) p 38

2 Pask, Edward H., Ballet in Australia: the second act 1940–1980 (OUP, 1982) p 45

3 Pillsbury, Edith, Lynne Golding Australian Ballerina (Allegro Publishing, 2008) p 39

4 Alida Glasbeek, who appeared as a Queen’s Page in The Sleeping Princess, went on to dance with the company before dancing internationally as Alida Belair, the name under which she also published her memoir Out of Step: a dancer reflects (Melbourne University Press, 1993)

5 De Vos, Audrey —entry in The International Encyclopedia of Dance, Edited by Selma Jean Cohen and DANCE PERSPECTIVES FOUNDATION (OUP, Current Online Version, 2005)

6 Having worked with Dame Margaret from the late 1990s for over a dozen years on the Dance Creation Committee of the Australian Institute of Classical Dance, I experienced first hand her visionary perception to identify what needed doing to achieve an objective and then to formulate an effective practical response.